The malleability of dog DNA is extraordinary. Cats of all breeds look more or less alike but a chihuahua and a Great Dane don’t look anything like the same species. Canis lupus familiaris has been living with us and serving us for perhaps 23,000 years. Unconsciously employing the same mechanisms that underlie evolution, humans have selected the canine characteristics they desired to accelerate change. Dog personality was pushed towards a more puppy-like mentality from the cold detachment of an adult wolf, making them more suitable as domestic companions – and less dangerous. Russian research has shown that this personality adjustment can be achieved quite quickly in wolves. Even diet has been manipulated and the domestic dog can digest starch entirely unsuitable for other canids.

In spite of the domestic felid’s familiar habit of torturing their captives, in the wild, most cats kill their prey quickly after an ambush or brief pursuit. Lions are the exception to these solitary feline hunting methods. Wolves on the other hand are certainly pack animals and their hunting technique is a relentless pursuit of the herd to identify weak, old or sick individuals. They have an exquisite sense of smell. Death when it occurs is not quick or pleasant. The pack catches and pulls down the much bigger ungulate by targeting the soft parts. Wolf pack hunt success rates are in fact low. Perhaps one in twelve hunts for moose end in a kill and wolves are adapted to a famine-or-feast existence. They are also at risk of injury during a hunt. Pressure from these predators keeps the ungulate population fit, healthy and numerically sustainable. The recent reintroduction of the grey wolf to Yellowstone had an astonishing and very rapid positive effect, a so-called trophic cascade, forcing changes in the behaviour of elk that has benefited the whole environment with marked diversification of both plant and animal species.

The physical features of dogs were initially selected for utility in hunting or defence situations. The ancient Roman bodyguard the Cane Corso, the Dobermann and the Rottweiler were all developed for the protection of their owners or their property. Great Danes were bred big enough to tackle wild boar. (These dogs are actually German mastiffs. Their name was changed, like that of the Alsation, because of anti-German feeling.) Sighthounds became fast enough to run down prey too swift even for wolves to catch. Wolfhounds and deerhounds grew huge and lanky with long rough coats. Short-legged terriers could follow their quarry into the earth – as their name implies. I feel the Cane Corso with its traditional cropped ears would have been a better choice for the Devil’s hellhounds in The Omen than the rather pleasant-looking Rottweilers they actually used.

The appalling ‘sports’ of dog fighting, bull- and bear-baiting produced ferocious animals with immense bite pressures and extreme tenacity once they locked onto their victim. Animals with a back story like this do not look like good prospects for pets – unless you actually want to weaponise your dog. Recently some breeds’ more aggressive characteristics have been ameliorated by selective breeding but horrific attacks still hit the headlines.

Dog breeding eventually went beyond the practicalities of hunting, guarding, fighting and baiting. The desire to produce an appearance conforming to a seemingly arbitrary breed standard has resulted in characteristics that make some dogs unfit for a normal active life. It’s the kind of unhealthy obsession that led to abominations like the tumbler pigeon. Flat-faced (brachycephalic) dogs have trouble breathing, eating and panting – but look cute. They also suffer eye and skin problems. The short-legged Dachshund, bred to hunt badgers, ended up looking like an achondroplastic Doberman – but looks cute. Dachshunds have spinal problems and the inexplicable desire to have a German Shepherd’s back slope downwards towards its rear legs has left them with spinal trouble too.

The first dogs I knew were working collies on the farm rather than pets. My grandparents had two grey and white long-haired collies called Mac and Spot. At bedtime we thrilled to tales of their bravery in tackling vicious hedgehogs or herding foolishly reluctant ducks into their house for the night. Great sagacity was attributed to them.

My uncle had a classic short-haired black and white Border Collie called Nell of whom I was very fond. A railway line ran past the end of our farm road. The main road crossed over it by a nearby bridge. Nell met her end by vaulting the parapet of this bridge, mistaking it for a fence, and plunging onto the tracks below.

Not all the farm dogs were as friendly as the late Nell. One of them had David Bowie-style odd-coloured eyes and would rush to the limit of its chain to snarl and bark at us if we came near, nose up-turned and lips curled back from its teeth. I resented this no-go area around the shed where it was tied up. In frustration I fired a light, dried, herbaceous plant stem at it using my home-made rowan bow and was horrified to see it snag in its thick coat (with no skin penetration). Scared I would be caught abusing the dog, I screwed my courage to the sticking place and advanced on my opponent. To my surprise he let me disentangle the stick without so much as a whimper and we got along fine from then on. Not that I recommend shooting arrows at dogs as a training method… Even allowing for the fact that domestic dogs can digest starch the collies’ diet of bruised maize and milk did not seem adequate. I never saw them given any meat – but they did get butcher’s knap bones from time to time.

When I was a child we still had hill farms on the estate and watching the shepherds work the dogs was fascinating. Our shepherd put a small metal plate with a hole in it into his mouth in order to whistle but my father could make a piercing whistle without any artificial aids, not even his fingers. I have always needed to use my fingers for a proper whistle. Most enjoyably there were often collie pups to play with. The shepherd would note which ones naturally set about herding the hens in the yard as an indication of whether they would make good working sheepdogs. My mother was averse to dirt and smells and would never allow dogs or cats of any age into the house.

Most farms would have a smaller dog as a house pet and ratter in addition to working collies. My grandfather told me he set up a slate with a pull-cord in the byre to cut off the escape route of rats eating the cows feed at night. He then put his terrier in for a gleeful slaughter of the thieves. People forget the practical purpose these dogs were bred for and seem surprised if an occasional dopey grey squirrel fails to escape their pet. In addition to his collie my uncle had a Corgi called Wendy who was adept at finding hedgehogs in the woods. We would roll them up in hankies to take home. The spines would stick through like Mrs Tiggywinkle’s cap. We noted the hedgehogs were well-colonised by fleas.

Our farm mechanic, Bill, liked to shoot and owned a Golden Labrador called Biddy. He brought her to work with him so that his three daughters wouldn’t ‘spoil’ her. He kept a Cairn Terrier at home to occupy them. Biddy was amazing. She was devoted to Bill and a brilliant retriever. He would tease her by ordering her to ‘fetch the screwdriver!’ She understood ‘fetch’ but obviously had no idea what object Bill desired. Frantically she would bring him a variety of things lying around the garage workshop until by chance she picked up the screwdriver. Bill would make a big fuss over her success and Biddy would be ecstatic.

To train her, Bill would send her to the back of the garage where she couldn’t see what he was doing then throw a rag doll, a familiar toy of hers, far into the adjacent stack yard with its long grass and weeds. After making her wait for the command he would release her to quarter the stack yard, nose down, until she found the doll. She was infallible on a shoot, retrieving everything Bill shot and some birds other dogs had missed.

Finally, under constant pressure, my mother relented and allowed us a dog. It was to be my younger brother’s pet primarily. He wanted a Beagle. They are lovely looking dogs but I would not recommend a pack hound as a pet. They don’t even bark properly! The Beagle he chose was the dominant pup in the litter, reflected in his name: Winston. With hindsight this was also a mistake.

Bill the mechanic demonstrated that Winston was prepared to defend his food if challenged and told us we would have trouble if he did not learn to accept removal of his bowl while he was still eating. Winston remained obstinate and at times aggressive about meals and once bit Granny on the ankle when he thought she was interfering with his breakfast. I suppose the adults present should have been more forceful.

Typical of Beagles, Winston was not content with the entirely adequate diet we supplied and would sneak off to eat the cows’ ‘cake’ (processed feed) from the troughs in the byre. He would continue eating until he was so stuffed he could barely walk. He once disappeared for a few hours to return bearing a whole salmon wrapped in greaseproof paper. The farm was a mile from the nearest town and the mystery was never solved. No one from any of the farm cottages reported a theft. His attempts to dominate those around him finally ended after a confrontation with an off-the-lead Alsation while on a walk up the back road. He was never the same.

Our daughter was very keen to have a dog but while we were both working I felt this would be unfair to the animal which would have to be left alone during the day. We would also, by necessity, have to exercise it before and after a tiring day at work. Eventually my wife retired and I was working part time, so we relented. Our daughter accused us of deliberately waiting until she had gone to university but it was a practical decision. We needed the exercise.

The question then arose of what sort of dog to get. Obviously the right thing to do would have been to adopt a rescue animal but I was worried about the psychopathology of some of these dogs, many of whom had been badly treated or allowed to develop bad habits. There was also enough of the farmer in me to admire the look of pedigree stock and be put off by the chimeric disorder of mongrels. We also decided we wanted a ‘proper’ dog, not some deformed lap animal. An artist friend of ours who only paints outdoors kept a Hungarian (or Magyar) Vizsla for a companion while he was out and about. She died at an advanced age having become attractively ‘sugar-faced’ as Vizslas do.

He replaced her with a wire-haired variety, as the original with her thin coat was vulnerable to cold weather. Smooth-coated Vizslas only have one layer of hair and cannot be kennelled outdoors in a cold climate. We did not intend to keep our dog outside. Our artist friend was fulsome in his praise of the breed and strongly recommended we get one.

Using the Kennel Club website we located a breeder near Loch Lomond who had a litter for sale. While expecting all the pups to be spoken for we made enquiries. The breeder said she might have one dog and would call us back the next day. This sounded odd – but it turned out one of the pups was due to go to what the breeder considered was an unsuitable home and, furthermore, the buyer had delayed picking it up for frivolous reasons. We were told we could have this pup instead. Accordingly we went on a visit to Loch Lomond to see the litter. We thought we were inspecting the breeder but it turned out she wanted to have a good look at us!

We picked him up at eight weeks old. He was the last to leave his mother who leapt into our car before we departed as if she wanted to check us out. We set off for Edinburgh with him on my wife’s lap. Shortly after this the pup was sick but he would turn out to be a very good traveller eventually.

The first hurdle was what to call him. I wanted to go for something Hungarian and favoured Béla – as in Bartók, but our daughter said she didn’t want to have to explain why the dog had a ‘girl’s’ name – or have to shout ‘Béla!’ on Blackford Hill. In the end we compromised and settled on Louis for some reason. It seems to suit him. He has been subjected to many variations since then: Ludwig, Luigi, Luigi-Mo and even Lulu. He proved very easy to house train, taking less than a week, and has remained fastidious in his habits ever since.

The subject of neutering your dog is a fraught one. The primary benefit has to be the avoidance of unwanted litters, but it also removes the possibility of testicular tumours and benign prostatic hypertrophy in older dogs. It may reduce ‘humping’ activity and roaming but this is not certain. From a theoretical point of view, and being familiar with the appearance of geldings and bullocks (and castrati), I thought doing it too early might result in an overgrown animal with skeletal problems. In the end we waited until well after growth had ceased and had him done at 18 months. I cannot rid myself of feelings of guilt about this assault. It was distressing to sit with him in the vet’s waiting room after he was sedated and watch his bewilderment as he struggled to remain upright on jelly legs.

‘Entire dogs’ still seem to me to have a more taught, muscular, disposition. A lovely dog, a Weimaraner cross, whom we sometimes meet, has also been ‘done’. We asked his name once and were told he was called Fidel. ‘He’s been neutered, so now we call him Fidel Castrato,’ said the owner cheerfully. What a splendid joke I thought. Maybe the chap’s a writer. A few months later the James Bond film Die Another Day was on TV while I was pottering about. There was a scene in an outdoor café where the villain points the gun at a waiter called Fidel’s groin and says, ‘Now round up some more girls and take them to Room 42. Unless you want to be known as Fidel Castrato’. Fidel the dog’s owner was a plagiarist!

I would have to say that a Vizsla is not a suitable beginner’s dog. Vizslas are a very ancient breed kept by Magyar aristocrats for hundreds of years and exchanged between them as gifts. They have boundless energy and were bred to follow a mounted huntsman all day. After the two world wars and the associated devastation of Hungarian society Vizslas were down to a few hundred specimens and were in danger of extinction as a breed. In view of this shallow gene pool great care has been taken with blood lines in rebuilding their numbers to their present huge popularity. However, some English and American specimens seem a bit too skinny and nervy to me. Louis comes from solid Hungarian stock and is now calmness personified.

Rather like choosing your child’s name, what you think will be an original and fashionable selection often turns out to be common as muck – and Vizslas are now ubiquitous. Everybody knows about the ‘velcro dog’ nickname. I have to say Louis is not prone to their typical habit of climbing on top of you at every opportunity, but he does like to be with you all the time. Vizslas are in the ‘hunt, point, retrieve’ group of utility gun dogs – and all that that entails. They are scent hounds, obsessionally exploring the aromas of town and country. They point. They have a very strong prey drive and will pursue anything; suitable (squirrels and rabbits) or unsuitable (cats). In five years of trying, Louis has only caught one squirrel. At first nonplussed to find it in his mouth he did despatch it fairly quickly then shot off. He wouldn’t give it up but returned empty-mouthed quite quickly. Too quickly to have eaten it surely. Retrieving, at least in Louis’ case, is not such a strong trait. At most he will fetch a ball three times before becoming bored and setting off on some new, more engaging olfactory exploration.

The first 2 years of ownership were testing. Inevitably it started with the chewing thing and the the razor sharp puppy teeth took a toll on our hands and chair legs. It was a blessed relief when the adult teeth with their blunt points came in. Then there was the boundless energy. In the early days of puppy walking we met a chap in the street using a theodolite. As Louis hauled us forward, nose to the ground the man made it clear he wanted to engage with him. He had an eastern European accent. “My sister has Vizslas,’ said the chap, laughing. ‘Vizslas are like pup till five!’ This was a depressing but accurate analysis.

Having a dog means frequenting unusual places in all weathers. Louis has an comic aversion to rain. He doesn’t like casual water either and avoids puddles. In the end Louis calmed down a lot and, if a reward is pending, he is flawlessly biddable. He has a sweet nature but is a bit forward and tends to greet visitors with a good sniff around their perineal areas. At 32 kilos he can have you off your feet in an unguarded moment should a squirrel or cat hove into view. His tail is heavy and thrashes about in company – at coffee table level. Our first experience of entertaining with him around resulted in the near clearance of the fizzy flutes on the drawing room table. We are wiser now.

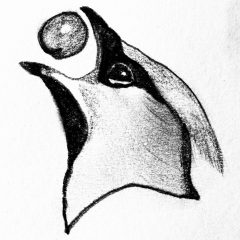

In a coffee shop near our house there were a number of charming dog portraits by a local (Australian-origin) artist called Kelly Stewart. We asked her to do Louis and were delighted with the result. He now stares calmly at the front door from the wall above the kneehole cabinet, greeting everyone as they come in.