My friend Rob and I wanted to try the famous wines, the ones that always seem unjustifiably expensive. Could they really be that much better than our regular, affordable, choices? When our consultant posts separated us by a few hundred miles we decided to each put £5 a month into a wine fund. It was a light financial burden that would allow us to have special wines, with a meal, every year or two. Once the pot had built up, Rob went to his wine merchant in Colchester and asked them if they had anything interesting. In that way we were able to indulge in some spectacular bottles.

My early experience of wine was nil. My whole family were very presbyterian. My father was even an elder of the Kirk. He hardly drank alcohol at all, but he had a very sweet tooth. When he did have a drink he liked Harvey’s Bristol Cream Sherry, Asti Spumante or a Sauterne called La Flora Blanche. I had tried the sweet Italian fizz, but never the Sauterne. Out for a meal with my then girlfriend and her parents, her father asked me if I had any thoughts on the wine list. The only thought I had was that I recognised the name La Flora Blanche there. I said my father liked it, so a bottle was ordered. Of course it was unbearably sweet and totally unsuitable for drinking with the main course. I was embarrassed.

When my grandmother died, her flat in Ayr was cleared. Like my parents, my grandparents almost never took a drink; my granny’s brother and father having been rather too fond of the stuff. She was always exhorting my mother not to let us have strong drink in case we, ‘got a taste for it.’ Like my parents, they would perhaps risk a sherry at Christmas.

In Granny’s posthumous sideboard were some bottles of wine she’d been given as presents but never consumed. I inherited a bottle of champagne and a bottle of a red wine called Chateau Figeac. Both bottles had been left upright and ignored for years. The vintage of the red was sometime in the sixties; 1962 I think. Some years after acquiring this legacy I chilled the champagne and opened it, only to find the cork had shrunk and the wine was flat. By that time I did know a little bit about wines and the major grape varieties. I knew that fresh air was bad for reds. I reckoned that the Figeac, having been stored in the same way, would be a treacherous bottle to serve to guests and left it in the cupboard under the stairs for a few more years.

My brother came to stay with us while he was between properties. One night, the three of us got carry-out pizzas for supper and I discovered we had run out of our usual red. My eye lit on the Figeac. Here was a chance to try it without fear of letting any dinner guests down – so I opened it. The cork was tight and smelled lovely. I tasted the wine, and it too was lovely. The three of us drank it, reverentially, around the coffee table, over our pizzas. At the time, it was the best red wine I had ever drunk. It was a lesson learned. I checked online while I was writing this piece and the current price quoted for a bottle of 1962 Figeac is £273.

Rob set about doing wine and restaurants with the same enthusiasm and dedication he had brought to fell running, top level chess, military history, castles, birdwatching, abstract expressionism – and medicine. He discovered a restaurant-with-rooms in Kingussie called The Cross, run by Tony and Ruth Hadley.

The restaurant was housed in a charming Victorian shop on the High Street. In the front was seating for pre-dinner drinks around an open fire. The tables were in the rear. Ruth, impossibly, cooked in a tiny galley-type kitchen buried in the depths of the building. The food and accommodation were ridiculously good and ridiculously cheap, although prices rose as the rave reviews and awards followed. At the outset, Rob could save up for a visit by putting his loose change in a jar every day. It was the most fun you could have over a weekend. We went as often as we could, frequently with friends. The scent of birch logs in the air on an autumn afternoon, as we parked the car across the street and checked in, acted as a Pavlovian appetiser. Ruth cooked brilliantly while Tony did front-of-house and the wine. After a marvellous meal, all you had to do was find your bedroom.

I still have the menus, but the food is a topic for another time. The way the Hadleys ran The Cross was very onerous. In addition to the main event of the evening, they did breakfasts every morning. Every year they took a month off to visit their beloved France, recharge their enthusiasm and find new ideas. That is, they did until France restarted nuclear testing in the Pacific. That did it for Tony. To the amazement of national restaurant critics, he stopped buying French wines completely. ‘They aren’t testing their weapons in Entre-Deux-Mers or the Loire,’ he declared.

Rob would pass me his Hugh Johnson Pocket Wine Book annually when he bought a new one, but it was at the Cross that we did our serious wine research. Tony was happy to help out. He once gave us a vertical tasting of three vintages of the New Zealand super star, Cloudy Bay. At the time, some considered it the best Sauvignon blanc in the world. The wines were all gorgeous, and subtly different in character. In 2003 Cloudy Bay was acquired by the champagne house Veuve Clicquot, who increased production and, in my opinion, decreased the quality. I think it is now over-priced for what it is and trading on its illustrious name. We also learned that kicking off an evening with a bottle of methode champenoise between four of us before the meal was perhaps a mistake. On one notable occasion the fizz was a Jansz from Tasmania. By the time we negotiated a ‘flat white’ with the early courses and arrived at the red wine, our powers of discrimination were markedly impaired.

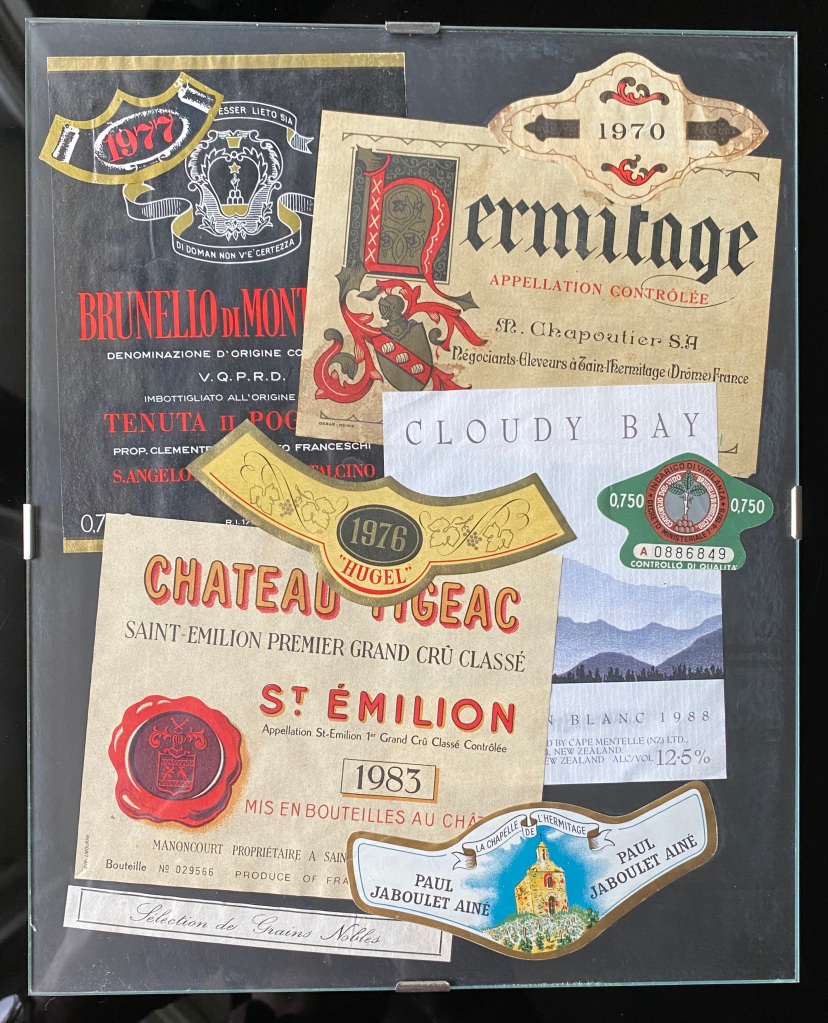

The trouble with wines is that they are consumer goods. You can keep them in a collection like stamps or coins but basically you ought to drink them. Like burning a Picasso, once it’s gone it’s gone, and all you have left is a fading memory. And like twitching, it’s an evanescent pleasure; intense but transient. You can of course keep the labels – like taking photos of a rare bird – but these are just mementos. For a while, we soaked these stylish bits of paper off our favourite bottles, and after a debate about who should have them, stuck them in albums or, in my case, a collage. Chateau Mouton Rothschild would commission famous artists to do their labels which changed with the vintage. Curiously, the labels from the better vintages are less collectible than the poorer years. This is because the less desirable years get drunk quickly and so those labels become rarer. Rob kept the Marc Chagall label from our bottle of Mouton Rothschild 1970.

There is a modest, but excellent, Turkish restaurant near us in Edinburgh which has two framed collections of labels from some of the world’s most famous wines. Wines like Mouton Rothschild, Petrus, Chateau Latour and d’Yquem. I asked the owner and chef, Gursil, where he got them and, rather indignantly, he said, ‘I’ve drunk them all!’ Astonished, I cautiously asked how he could possibly have afforded them. He said he had been a chef in top restaurants in London for many years. High net worth diners would order the most expensive wines on the list as a demonstration of their spending power but frequently left them unfinished!

Other memorable wines from the days of the old rugged Cross included a Tollot Beaut from Chorey-Les-Beaune, a great vintage, of which we eventually finished all the examples in Tony’s cellar. Later we bought other vintages of the same wine but they were never as good. Tony said new, stricter, regulations had been introduced under the appellation d’origines contrôlée (AOC) system which outlawed blending in any grapes from outwith Burgundy. Apparently in the past you could augment your wine with imported grapes from other areas of France, like Bordeaux. The net result of these new restrictions was a thinner, rather disappointing wine.

There was also a stunning Macon Villages Cuvée Botrytis dessert wine. Burgundy is not noted for its sweet wines but in certain years, when the conditions are right, grey botrytis (pourriture noble, or the ‘noble rot’) attacks the Chardonnay grapes. It extracts the water and pushes up the sugar content. In Italian vin santo, the sugar content is increased simply by drying the grapes, while the French sweet wine grapes are actually mouldy. Fermentation proceeds to its maximum, the point where the alcohol content stops the yeast growing, leaving much of the sugar unconsumed. The result is the exquisite sweetness with autumnal ‘fungal’ overtones that make these wines so interesting. Tony told us a tale about the owner of the vineyard concerned. Having found that his grapes had become infected during wet autumn weather, he phoned a pal of his in Sauternes to ask for advice. The pal came to his rescue and they made a unique sweet wine. Researching this phenomenon online, it seems a Cuvée Botrytis is actually a rare, but nevertheless regular, occurrence in the Maconnais.

There is mystery about wine and its country of origin. Wines drunk in situ, where they are produced, always taste better. Chianti Classico, Barbera d’Asti, Barberesco, Altesino and Brunello di Montalcino all taste fabulous in Italy – but when you get home, and buy the same wine in the UK, it never reaches those heights. Is it the weather, or the atmosphere, or do they simply keep the best grapes for themselves? The same is true of the more humble French Rosés. When on holiday in blazing hot Provence they are unbeatable and indispensable. Drunk cold on a chilly June afternoon in Edinburgh they often just make you shudder.

In Edinburgh, our favourite restaurant was Daniel Wencker’s L’Auberge in St Mary’s Street. It is now David Bann’s vegetarian establishment. Before we had children we often went for lunch on a Saturday followed by a pleasantly enhanced shopping trip. As regulars we were known to the staff and I was once asked to minister to one of the trainee chefs who had collapsed in the kitchen.

One day, our waiter came to our table and said, ‘Dr Stevenson, would you know the playwright Arthur Miller if you saw him?’ It was then that I realised that the distinguished-looking, and strangely familiar, man at the next table was Miller. At that time, a season of his plays was running at the Lyceum and Kenny Ireland had taken him and his partner out for lunch. Years later I discovered he had been put up in my cousin’s flat in Northumberland Street which she rented out through the Scottish Arts Council.

At L’Auberge we usually started with a half-bottle of a particular Chablis to accompany the starters. One day, when I asked if we could have it, the waiter said, ‘No you can’t.’ Puzzled, I asked, ‘Why not?’ ‘Because you’ve drunk them all,’ he replied.

The special Rob and Allan Wine Fund trundled along in a satisfactory way but more widely-spaced visits resulted in even greater sums accumulating in the account. We splashed out on increasingly expensive and illustrious stuff. Great white Burgundy, classic Bordeaux reds, stunning Australian reds (like Penfold’s Grange; the bouquet could be detected all the way across the room), and fabulous pudding wines. We had Chateau Gilette (aged in concrete vats), a Chateau Rieussec, and a half bottle of d’Yquem which cost us £61 in the Nineties.

Eventually, children and work commitments made further oenological experiments impractical and reluctantly we wound up the account. Our final round of bottles was the best we could remember and the realisation that we just wanted to repeat those choices next time told us we had reached the end of a very pleasant road. Our final red was from California, a Ridge Monte Bello ’78. This was actually the best red I have ever drunk, better than the Figeac.

It was a great regret that on our trip to Califiornia we weren’t able to fit in a trip to Ridge Vineyards, perched on the Monte Bello Ridge south of San Francisco. In any case, I would have had to drive down there, rendering the visit pointless. Rob’s sister lived in San Francisco for a while and joined the Ridge tasting programme. The vineyard organised vertical tastings of their wines, including the Monte Bello, for their members. These were accompanied by live jazz and a paella cooked en plein air. Rob has been to one of those.

One of the drawbacks of taking a pretentious interest in wine is that kind people inevitably give you special bottles. I usually write the name of the donor on the label, then carefully put it in a rack on the bottom shelf of the dining room cupboard for later consumption, meanwhile carrying on with the usual Cavas, New Zealand Sauvignon Blancs, Riojas and good Italians. Every now and then I might push the boat out and have a Royal Tokaj with dessert.

The wines in this ‘too good to drink cupboard’ have been neglected for fear of another Figeac incident. I have now decided this has to stop. Along with my sense of smell, my palate is definitely deteriorating and those two abilities are inextricably linked. Like me, some of the wines have started fading with age and the fear is that a few may have gone over completely. Therefore, they must be drunk – and we must be drunk – before it’s too late.