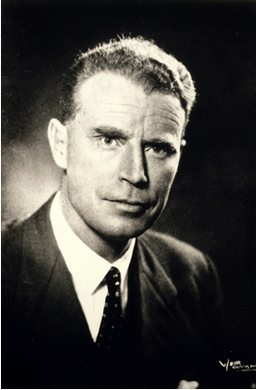

A third generation Scottish doctor, Ian Donald was mentioned in dispatches during the war after he pulled several airmen from a crashed and burning bomber. The bombs were still on board. As Regius Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Glasgow University in the 1950s, he thought industrial ultrasound scanners might be adapted for use in human subjects. They were. There is a famous picture of him scanning his pregnant daughter. At the end of his illustrious life, he worked for a while at the Western General in Edinburgh. I was told he estimated how much diuretic he needed to take for his cardiac condition by scanning his inferior vena cava in the morning.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ian_Donald

Technique

A back-of-an-envelope calculation indicates I have performed ultrasound scans on about 40,000 people in a 33 year-long radiology career. This would be a decent gate for a sporting event and enough material to have seen most things ultrasound can reveal. I did at least two ultrasound lists per week of up to 25 patients plus ad hoc scanning at other times. A list had to be completed in under four hours, which left no time for slacking. Ideally, you set up two ultrasound rooms with an ultrasound ‘helper’ to get the patients onto the couch and ready to go. You could then move rapidly between the rooms and maximise your scanning time. Having a junior trainee with you whose scans needed to be checked slowed you down considerably. Underlying all this intense activity was the necessity of getting it right.

You need experience to interpret what you are looking at on an ultrasound image. To the tyro, the ability of a senior radiologist to recognise pathology instantly seems almost psychic. With common conditions the diagnostic experience is akin to recognising an old friend; with rarer ones it’s more like meeting a celebrity. The secret to success is putting in the hours – and maybe a little bit of aptitude. You can learn to play a piano if you can learn to type, but genuine musicality needs talent.

In the second year of our radiology training we were allowed to start doing ultrasound. To me, the process seemed magical and it remained my favourite technique. The silly description of it as ‘putting jelly on the belly and watching the telly’ degrades the wonder of it all. Like a magic wand, you pass the probe over the body and a fan-shaped image of the organs lying under the skin appears in real time on the monitor.

An ultrasound signal will not cross an air gap. The probe needs a coupling medium to both conduct sound into the body and to receive the returning echoes. Early techniques used a water bath, but ultrasound gel is a lot more practical. The time it takes for the echo to bounce off a structure and return to the probe places that signal at a specific depth and from that data images are constructed. The physics and electronic engineering of all this is very complex. Modern probes have no moving parts; multiple piezoelectric crystals are arranged in an array in the head of the probe. These crystals emit ultrasound and respond to the returning echo by emitting a tiny electric pulse.

The triangular image seen on the monitor tapers upwards towards the position of the probe on the skin surface and is rendered in monochrome. You can scan the patient at any angle you please. Scanning in the sagittal plane – the long axis of the body, front-to-back – shows you the organs from the side. Similar to the air-filled spaces outside the body any air present in bowel will also interrupt the signal and prevent visualisation of any structures behind it. So will bone, which is impenetrable to ultrasound. Like bone, the stones found in fluid-filled organs like the gallbladder and urinary bladder will reflect the sound beam and cast a diagnostic dense ‘acoustic shadow’ behind.

The higher the frequency of the sound, the greater the detail displayed but higher frequencies penetrate less depth of tissue. For that reason very high frequencies can only be used to scan superficial structures such as the eyes, the thyroid and the testes. The latter organs might well have been designed for ultrasound lying – as they do – outside the abdomen. The image resolution within these small superficial structures is remarkable, often described as ‘exquisite’ for some reason. Demonstrating larger structures like the intra-abdominal organs demands a lower frequency and some detail is inevitably lost.

When you first sweep a probe over a patient’s body there is a tendency to look at the probe or at the patient rather than the monitor display. You must learn to do the physical part of the scan automatically while concentrating on the images on the screen, similar to looking through the windscreen while driving a car.

I usually did a quick survey of the abdomen to get the lie of the land before scanning the patient in detail. Once, while doing a pelvic scan on a young woman, I noted a mature follicle in her right ovary. This indicates that ovulation is imminent,. That happens in an instant as the follicle ruptures. I scanned her uterus in the midline then across to her left ovary before returning to the right side where I noticed the follicle had started to collapse.

‘Do you ever get pain at mid-cycle?’ I asked her.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘In fact, I have a bit of a pain at the moment…’

Mittelschmertz (middle pain) is the medical term for the discomfort of ovulation.

Since the images generated are very thin two-dimensional slices you must learn to construct a mental picture of the organs you are scanning based on your anatomical knowledge. The three-dimensional structure of the patient’s liver, biliary tree, gallbladder, spleen, pancreas, kidneys etc is built up in your mind as you scan through them – like shining a torch around a darkened room and remembering what you’ve seen. Actual 3-D reconstructions of ultrasound data produce a confusing jumble of echoes too difficult to interpret and if you surface-render ultrasound it takes you back to square one. After all, the patients themselves are ‘surface-rendered’ structures that you cannot see through. The popular 3-D images of fetuses impress the lay person but are of limited diagnostic value. The concept that thin slices through a structure are easier to interpret than a 3-D image is difficult for non-radiologists to grasp.

Turf Politics

Clinicians would frequently ask me what the ‘trick’ was to ultrasound. I always replied that if you turned the film upside down the answer was written along the bottom. Obviously, the actual ‘trick’ is to do thousands of scans. Some images, particularly any measurements, are recorded for clinical record-keeping and as an aide memoire when reporting, but the crucial thing is your opinion rather than those tricky scan images. Clinicians have to trust the accuracy of your report, which is where the issue of confidence in an individual radiologist arises. Clinicians like to know which radiologist has reported their patient’s scan and they like to have critical scans discussed in joint meetings for clarity. Referral to a specific radiologist is very common in private practice.

After about two years of doing hefty ultrasound lists you begin to get the hang of it, and good enough to fly solo. For non-radiology-trained clinicians to become similarly competent would require them to undergo the same amount of training. Despite this, clinicians would sometimes have a crack at doing ultrasound themselves. They would get hold of some ‘soft money,’ buy their own scanner, then go on a weekend course at a hotel somewhere funded by the ultrasound manufacturer. As Arthur Conan Doyle once said, ‘mediocrity recognises nothing above itself’. A lack of insight into your limitations can result in mis-diagnosis and potentially harmful consequences for the patient.

Many years ago the general surgeons in the main hospital where I trained decided that they didn’t want to bother with radiologists any more. They felt they should crack on with doing their own scans. The consultant in charge of our service said that if they did that he wouldn’t be doing any more scans for them. A threat he would be unlikely to carry out. After the usual weekend course they bought their own scanner. They did not ask for any training from us. On the basis of ensuring safe medical practice we would have refused anyway. We had enough on our plate training our own juniors.

Some time later, on a Monday morning, the surgeons came down to the department and asked to speak to the boss. They were puzzled. They had detected gallstones in a patient at the weekend and taken them to theatre only to find that the gallbladder was quite normal. My consultant reluctantly agreed to look at their images.

‘See,’ they said, ‘There are the stones.’

‘Well, actually that’s the right kidney,’ replied my boss.

The surgeons stopped doing scans after that and abandoned their scanner. It is very wasteful to have a nice new US machine sitting in a corner under a dust sheet doing nothing. That does not happen in radiology departments.

An impatient but charming gastroenterologist once stuck his head round the door of the scanning room to ask if I’d do an urgent abdominal scan for him. At the time I was examining a baby’s head through the fontanelle (‘soft spot’) looking for any intracranial haemorrhage. When I spoke to him later he asked me what I was doing to the baby and was surprised to learn that US had this application. Out of devilment I asked him why he didn’t do his own scans to which he enquired how long it had taken me to become proficient at it. I said it had taken two or three years of scanning several lists a week. ‘Well, I don’t have the time to do that!’ he said. ‘I don’t do my own biochemistry and I don’t intend to do any ultrasounds. I prefer to get you to do it and send the patient back to the clinic with the right answer.’ As a gastroenterologist skilled in endoscopy, he had plenty of procedures of his own to do. Ironically gastrointestinal endoscopy has almost completely replaced the barium studies that were once fundamental to radiology practice – and a huge part of my own early training. The relentless advance of technology has swept many skills into the dustbin of medical history.

This is precisely what happened when lower limb venography was replaced by ultrasound. A swollen or painful lower limb can be the result of a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Most people are familiar with this as a complication of long-haul flights, but DVTs also occur in a variety of other clinical settings. The danger is that a clot that has formed in a leg or pelvic vein suddenly becomes dislodged and travels north, through the right heart and into the lungs. If the clot blocks the pulmonary arteries oxygenation of the blood fails and the consequences can be fatal. Smaller clots cause breathlessness and lateralised chest pain aggravated by breathing. Venography had been the way to detect blood clot for many years. It was the ‘gold standard’ of DVT diagnosis and clinicians were confident in it.

Lower limb venography is the injection of X-ray contrast into a small vein in the foot so that the larger deep veins of the legs and hopefully the pelvis can be demonstrated on X-rays. It produces hard copy in the form of radiographs that show recognisable veins. Ultrasound images on the other hand make no sense at all to clinicians, requiring them to depend entirely on the opinion of the radiologist. This makes them uneasy. The appeal to us was getting rid of venography – a difficult and unpleasant examination – and replacing it with ultrasound. Of course it was necessary to demonstrate that in addition to being safe and painless, ultrasound was at least as accurate a technique as venography.

Venograms were by definition always urgent and seemed to gravitate towards Friday afternoons. Swollen feet can make finding a vein very difficult. Touniquets were applied above the knees and ankles. If necessary the patient’s feet were heated with warm towels or a basin of hot water to encourage venous engorgement. Any swelling present had to be pressed away using your thumbs. Once you had established venous access the patient was positioned on an X-ray table ready to take films as the contrast was being injected. About 100 ml of contrast was injected into each foot as fast as you could manage. I used to hold the syringe barrels in both fists and force the plungers against the front of my lead coat. You hoped the rapid flow of viscous contrast would not blow the veins you had punctured. Two views of the calves were followed by blind films of the thighs and pelvis as you removed the tourniquets and lifted the legs up to encourage flow. The contrast would then travel up into the abdomen. There was some skill in knowing how long to wait before telling the radiographer to take the film.

We were keen to get rid of this awful test – but the clinicians were resistant. We presented our case at hospital ‘Grand Rounds’ supported by our own research and papers from the the world medical literature. Our research had involved doing a venogram and an ultrasound on every patient referred for venography to show that we were not missing any significant thromboses. We emphasised that we could also pick up other conditions on ultrasound that masquerade as thrombosis – like ruptured knee joint cysts. Venography could not detect these. Eventually we convinced our colleagues and succeeded in replacing the venography service with ultrasound. Ironically, clinicians soon perceived that US was a reliable benign, non-invasive procedure compared to venography and their threshold for requesting tests dropped!

Some specialties, cardiology for example, are limited to just one anatomical area. It had become clear to cardiologists that they would need to learn ultrasound of the heart and angiography of the coronary arteries to avoid simply becoming a referral service for radiology. All of that was inevitable, but without general training non-radiologists would not recognise other conditions lying outwith their own particular area of expertise.

The Passage of Time

The biggest change in ultrasound practice in my working lifetime was the emergence of radiographers, the radiology technicians, as diagnostic ultrasonographers. That role had previously been the preserve of the medically qualified radiologists. The pressure on radiologists to deal with the massive increase in workload from the new cross-sectional imaging techniques (CT, MRI and PET) had encouraged this trend. The British Medical Ultrasound Society is now largely a radiographer-led organisation.

Unlike the reporting of disembodied X-ray images, when you do an ultrasound you have a real live patient in front of you. You can take a history from them and even exchange pleasantries. After a glance at the clinical information on the request form (not always helpful) you scan what lies beneath. As things are revealed you can ask the patient questions in real time to help clarify the diagnosis.

Sometimes a returning patient would ask me what the scan was showing.They had grasped that you were making that decision at the time, as you would when feeling their abdomen or listening to their chest. ‘I hope you’ve got good news for me today doctor,’ was a common greeting as the patient entered the scanning room. I would never mislead anyone, but as I was not in charge of their ongoing care, imparting bad news to a patient could be problematic. At least if they were going directly to their clinician after the scan any issue could be promptly dealt with. An oncologist once told me it was ‘helpful’ if I’d given the patient the impression that all was not well. I felt that was actually their job.

Despite all this I looked forward to ultrasound sessions, even though they were invariably over-booked forcing you to work at an uncomfortable pace. I used to compare it to driving down the high street on a busy Saturday morning at ever increasing speed. How long before you miscalculated and hit a pedestrian?

Beyond the purely diagnostic work lie interventional ultrasound procedures. This is the use of ultrasound guidance to carry out treatments that would have previously required some form of conventional surgery. Examples would be the targeted biopsy of small, deep-seated tumours or the drainage of an organ or fluid collection. Surgeons have the advantage of an anaesthetist to put the patient to sleep and look after them while they do their thing. Doing this type of work as a radiologist meant managing the understandable anxiety of a conscious patient while simultaneously performing a tricky procedure under local anaesthetic. You could give intravenous sedation – but if the patient nods off, you’ve given them a general anaesthetic. Adequate analgesia is crucial if you are going to penetrate sensitive tissues with a needle or a drainage catheter.

Anecdotage

I once had to drain both kidneys in a very unwell patient and insisted on anaesthetic assistance. The disincentive is the delay that introduces to proceedings and the fact that the on-call anaesthetist may be busy elsewhere. By coincidence the anaesthetist who turned up was the same one who had done my wife’s epidural during the delivery of our second child. At the time I didn’t volunteer that I was a doctor, not wishing to put him off his game. He’d been rather tetchy, proclaiming that my wife would deliver soon enough anyway without the need for an epidural. At the time we were both quite annoyed with him. Once the kidneys were successfully diverted he complimented me on a promptly completed task and, frowning slightly, asked if we had met before. I explained that we had and outlined the circumstances. He asked if it had been a good epidural. I said it was and he smiled. After that we exchanged pleasantries when we passed each other in the hospital corridor.

The technical challenge of targeting small solid tumours in the deeper part of organs like the liver is considerable. The needle shaft is of uncertain visibility on ultrasound and, like a long shot, small errors at the outset can result in a miss. Core biopsy devices give a better specimen for the pathologist to look at but also put a bigger hole in the patient. I often took my own precious biopsy specimens along to the pathology lab to make sure I had hit the target – and to make sure they didn’t get lost.

A technique largely now taken over by radiographers is obstetric scanning. I learned to do these scans when I first took up my consultant post. The bulk of them are done to estimate the date of delivery but patients who experience early pregnancy bleeding need scanned for ‘viability’. A non-viable gestation means a difficult conversation followed by a trip to theatre. We were often contacted by GPs who wanted ‘a scan for reassurance’. I soon learned to ask the GP to tell the patient that if they’d had any bleeding there was a possibility that reassurance would not be forthcoming. In the end we insisted that these referrals went to the gynaecologists first for an informed discussion of the possible consequences before the patient attended for their scan.

Beyond simple dating scans routine scanning at 20 weeks was introduced to exclude fetal anomalies. As the radiographers’ training progressed, radiologists were no longer required to do the simpler dating scans. We were still called in to look at any potentially abnormal pregnancies the radiographers had detected. Obviously medicine is all about disease but doing simple dating scans in healthy mothers was a pleasure. When that evolved into only checking abnormal scans a lot of the pleasure went out of it.

Tyson

I was carrying out a routine anomaly scan in a small hospital I worked in as part of my first consultant post. The woman’s partner was in the room and was watching me closely. As I began scanning I became aware of the sound of a large dog barking menacingly somewhere nearby. I glanced towards the window.

‘I tell’t ye no tae bring Tyson,’ said the woman to her other half, annoyed. I carried on with the scan – which was normal. Although it is possible to detect the sex of a fetus it is not usual to offer that information. Apart from the possibility of making a mistake, there are some settings in which that information might be misused. If you were asked, it was easier to be sure the baby was a boy than a girl.

‘Can you tell tell whit it is doctor?’ asked the man. As it happened, I already knew it was a boy.

‘Well, yes. Are both sure you want to know?’ I offered. The man and the woman exchanged glances, Tyson continued to bark furiously in the background somewhere.

‘Aye OK then,’ said the woman.

‘Well,’ I said, smiling, ‘It’s a wee boy.’

The man erupted. ‘Aw, no anither laddie!’ he shouted.

‘Ah tell’t ye no tae ask!’ yelled the woman. ‘Ah tell’t ye!’

Technicolor

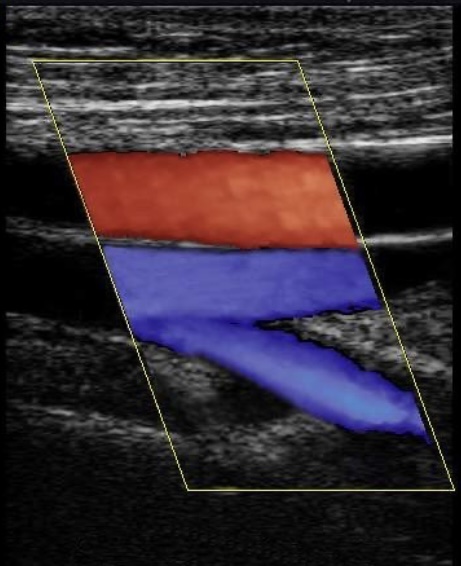

The exception to US yielding monochrome images is colour doppler. The doppler effect is that drop in pitch you notice when a noisy car passes you at speed. Rapid approach compresses the sound waves raising the pitch then, as the car departs, the sound waves are pulled out and the pitch drops. The same effect is produced by bouncing sound waves off moving blood. Simple doppler samples a limited volume within a blood vessel but multiple measurements can be made across a whole image and converted into colour signal superimposed onto the black and white image. By convention red is ascribed to movement of blood towards the probe and blue away, but this is arbitrary. The intensity of the colour can be made to reflect the velocity of the blood. Turbulent flow jumbles the colours and narrowing of arteries produces a jet of very high velocity.

I gave a workshop in Athens to the Greek Ultrasound Society Annual Meeting. A lot of physics was involved and I tried to spice it up a bit. As I waited to start my talk, which was to be illustrated by videos of colour doppler examinations, I ran a clip of Celtic and Rangers scoring against each other in quick succession during a recent Old Firm match. This got their attention but blue versus green wasn’t a particularly helpful analogy. My later illustration of Scotland scoring a try against Wales at Cardiff at least involved the correct colours. ‘Red is movement towards us, blue away,’ I declared. The Greeks were unimpressed with Rugby Union. A few of them were asleep.

After an hour and a bit of me droning on I took questions. There were just two and both were about whether colour doppler might be useful in the investigation of erectile dysfunction. At the time I didn’t really know. My colleague later said this reflected the pattern of private practice in Athens – no pun intended. I later found out that yes, colour doppler was useful in this condition and I even performed some of these tests myself. This involved injecting the offending organ with a prostaglandin-related drug. A certain amount of commitment was required of the patient in order to achieve a diagnosis. Priapism followed by extensive thrombosis was a potential side effect.

That evening, after my colourful lecture, a highly elaborate ceremony was held at Athens University. Choirs sang, music was played and they presented all the guest lecturers with a silver icon. Afterwards there was a grand reception with drinks and nibbles. It was December and quite chilly for Athens. There was a familiar odour about the place which for some reason reminded me strongly of my grandmother. I couldn’t place it until I realised that many of the women were wearing fur coats and the smell was of moth balls.

Röntgen Redux

One morning while attending the 8:30 clinical meeting with the urologists I was called out to take a phone call at reception. It was from a physicist who was an expert in subsurface radar. I’d never heard of such a thing. He had previously worked for the military and had a laboratory out in East Lothian somewhere. He wanted to explore potential medical applications for his technique. So far he had used it successfully to find sunken ships in the Mediterranean and unexploded WWII bombs for the London Underground. He asked if he could come and see me to discuss a clinical trial. When I returned to the meeting a colleague asked who had called. ‘I think I might have been talking to the next Conrad Röntgen,’ I joked.

A couple of weeks later he duly appeared and I showed him my best ultrasound pictures. He seemed very disappointed in them. He could see ‘down to molecular level’ with his radar and was baffled as to how we could determine anything useful with such primitive equipment. I asked him if it would help to see some live imaging and he said yes, he thought it might. It was lunchtime and the list in the room with the best scanner had just finished. When ultrasound reps are trying to sell you their machines they often scan their own bodies as a demonstration, usually their abdomen or neck. I didn’t really want to get ultrasound gel on my abdomen or my clean shirt so I decided I’d use my neck. I would be able to show him colour doppler on my neck vessels.

Picking up the high frequency probe I put gel on it and stuck it on my right carotid artery. The first thing I saw was an atheromatous plaque near the carotid bifurcation. ‘Oh,’ I said, dismayed.

‘What’s the matter?’ asked the boffin.

‘I’ve got atheroma in my neck.’

‘What’s that?’ he asked.

‘It’s the thing that causes strokes and heart attacks,’ I said bleakly.

‘Did you know you had that?’

‘No.’

Needless to say the radar thing never got off the ground and we carried on with our ‘primitive’ techniques. The plaque in my carotid bothered me. I had looked at the other side, which was normal. Helpful colleagues told me that they too had looked at their carotids and were delighted to report that their arteries were all perfectly normal. I went to see a friend, a radiology professor in the neurosciences unit, because carotid atheroma was one of her specialist research subjects. She said carotid plaque was a common finding in 47 year old men like me but if I wanted to get my cholesterol checked I could. After a while I got my GP to do it and it was up. We checked it again a year later and it had gone up again.

Eventually I seemed to reach that part of the nomogram that indicated a statin would do me more good than harm and so I started treatment. I would occasionally sneak a look at my plaque to see how it was getting on. To my surprise it changed completely after I started simvastatin, becoming much more echogenic and possibly flatter. Of course, this may simply have been coincidence and part of the natural evolution of my arterial problem but studies suggest that atorvastatin, which I take now, can reduce plaque build up and stabilise it. Maybe I wouldn’t be sitting here typing this drivel if it wasn’t for a certain eccentric scientist.

Testing, Testing

I was referred a patient with breast cancer. She was the chatelaine of a grand Highland estate and had initially been treated in London. Her oncologist had asked me to scan her liver for metastases. We had no previous imaging in Edinburgh and no previous reports for reference. She swept into the room and addressed me with great confidence. A scan of the liver for metastases was a basic request. We performed such examinations several times a day. As I scanned her liver I picked up two small, intensely echogenic (bright), lesions in the right lobe. They were very well-defined and typical of benign haemangiomata, tangles of fine blood vessels. These are found in about 10% of middle aged subjects, particularly women, and are frequently multiple. They are the commonest type of benign liver tumour. I would not normally mention them to a patient but noting their presence in the formal report is important in establishing a baseline for later imaging. There were no lesions suggestive of metastases.

‘Well, are you finding anything?’ the grande dame enquired.

‘No. Well at least nothing you need worry about.’

‘What do you mean by that?’ she asked.

It was clear I would have to mention the haeamnagiomata. She would be going straight back to the clinic with my written report.

‘You have a couple of benign things in your liver that are of no significance. Nothing else.’

‘Would you say they were haemangiomas?’ I was surprised to hear her use the technical term.

‘Yes, that’s what they are.’

‘Good, that’s what they told me in Harley Street.’

She had been testing me.

Judging by Appearances

One of the benefits of doing private practice is the much more manageable pace of the lists. You actually have time to think and time for some bedside manner. Captains of industry can be tricky to deal with as they are not accustomed to taking anything on trust and have a tendency to interview you and make a judgement about your ability.

A few years ago a young man turned up for a testicular scan at the private hospital. He came into the examination room rather diffidently, dressed in a very smart pinstripe suit. He was tanned and I assumed he was a ‘young urban professional’ who had been somewhere expensive and sunny for a holiday. I greeted him and he nodded without saying anything. It is very common for patients attending for this examination to be highly embarrassed. I explained that he needed to loosen his trousers, get onto the couch then slip his pants down to mid-thigh level. Again, he said nothing. The scan was quickly performed and entirely normal. I handed him some paper tissues to clean off the gel.

‘That’s all fine,’ I said. ‘Everything is normal and I will send a report to your doctor.’ Again, he nodded but said nothing. He finished adjusting his apparel and I turned away from him to face the scanner and close his case, ready for the next patient.

‘So ye’re a ba’ man then?’ a broad Scots voice enquired.

‘Pardon?’

‘You’re a ba’ man. That’s whit ye dae?’

‘Well, it’s not all I do…’

‘Aye, we yase the ultrasound on the yowes, ye ken.’

I glanced down at the request card to see the address of a Borders farm.

Finally

I miss the magic of ultrasound. I have been scanned by colleagues and had the weird experience of lying on the couch wondering what they are seeing on the screen. In addition to scanning themselves, many younger colleagues scanned their wives during pregnancy, a practice that should properly be discouraged. I intended to avoid doing that with our children but during her first pregnancy my wife was concerned that she hadn’t experienced ‘the quickening’. In fact she had, but misinterpreted it as something else. This was all terra incognita to me.

Since she had already had a normal detailed scan I thought there would be no harm in having a recreational look at the baby. We went to the department one evening and as soon as I began scanning I saw there was an obvious cystic abnormality in one of the baby’s kidneys. The other kidney was normal as were the rest of the organs. There was urine in the bladder and a normal amount of liquor. The pregnancy was only 20 weeks duration at that point. We went home and I called a senior colleague. The next morning he confirmed the findings which had been overlooked at the detailed scan. 20 weeks of worry and further scans ensued before our healthy son was born – albeit with only one kidney. The knowledge of having a single kidney may be crucial to him in the years to come so I tell myself it wasn’t really the wrong thing to do. However, as one of my old consultants told me during my house jobs, ‘Never have a test unless you know what the result is going to be.’ Wise words.