In the Midlands and north of England wasps are commonly known as jaspers. No one seems to know exactly why. Is it a phonetic corruption of ‘vespa’ or a just the similarity in colouring to the mineral jasper? Maybe it’s a reflection of the wasp’s perceived character – like a moustachioed Victorian bully called Jasper. This presumed nastiness is reflected in our usage of ‘waspish’ as an adjective for unpleasant things – like a sarcastic sense of humour or a prickly personality. In America wasps are known as yellowjackets. Wasps exhibit aposematism, a warning coloration. Having noticeable jazzy colours helps other animals avoid being stung and the wasps avoid being eaten.

The Italian for wasp is vespa. Anatomically they are sharply divided into head, thorax and abdomen with only the slimmest ‘wasp waist’ connecting the latter two segments. Close examination of their black and yellow exoskeleton makes you feel that they are actually more evolved than we are. They are perfect, tiny, armoured flying machines carrying sophisticated weaponry. When aircraft manufacturer Enrico Piaggio saw the first post-war prototype of the scooter his company would take to world-renown, he exclaimed ‘Sembra una vespa!’ – ‘It looks like a wasp!’ – naming his product instantly.

Now is the time the vespal queens over-wintering inside our houses start to emerge from their torpor spent in the folds of our curtains and pelmets. We have had fewer dormant queens in the house than usual this year; just the one in fact, found clinging to the curtains in the drawing room a couple of days ago. I trapped her using a glass tumbler and a postcard and released her from the bedroom window. She cleaned her antennae briefly before zooming off over the garden.

Having emerged, the queens seek a site to build their grey papier mâché nests. The legend is that the Chinese invented paper after observing wasps chewing wood to make their nests. The rasp of their jaws on dead wood is audible to us. Typically they use old fence posts and decaying garden sheds as substrate. Wasps nests are called bykes in the North of Britain. They build them in hollow trees or in animal burrows and sometimes in the roof spaces of our houses. As a boy I can remember my father getting one of the men on the farm to destroy a wasps’ nest by pouring petrol down the burrow and igniting it – a tricky operation.

During the winter, as logs are brought into the house, sleeping queens come with them. Roused by the heat of the room they appear without warning, cruising around the Christmas cards and tinsel. They are magnificent insects and I never have the heart to kill them. I return them to the biting cold of the log store with no great expectation of their survival after this premature end to their suspended animation. I suspect they burn up too much of their stored fat in the false hope of refuelling from spring flowers.

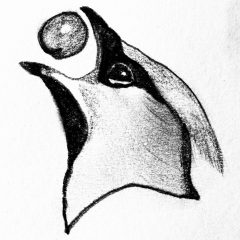

Wasps are social insects related to ants and are said to exhibit reasoning (New Scientist 8 May 2019). In Britain there are about 9,000 species of wasp but we are only really familiar with the common wasp (Vespula vulgaris) and the German wasp (V germanica). They are very difficult to tell apart. The german workers have three black spots on the face. Wasps are pollinators and also useful predators of insect pests such as caterpillars and aphids and they should be left in peace.

The vigorous cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus) familiar from shrubberies contains toxic amounts of prussic acid – hydrogen cyanide – which is the reason the cut leaves and stems smell faintly of almonds. Crushed leaves in a jar can be used to kill insects. It is said to be too slow a method to use on butterflies and moths who damage themselves as they struggle in their death throes. An artist friend of mine, Jim Dalziel, has an interest in entomology and once spent a summer afternoon capturing wasps and putting them in a jar with shredded laurel leaves. Once they keeled over he was able to use a magnifying glass to work out which were the german ones and which the commoner vulgaris variety. When we came round later that evening for supper he was keen to show off his new skills and invited me into his studio. Retrieving a folded-up piece of drawing paper from the bin, he opened it, promising to show me the key identifying features. It was immediately apparent to both of us that the numerous wasps had only been anaesthetised and were now quite annoyed to find themselves trapped in a paper prison. We rushed to return them to the garden before they attacked the unsuspecting company.

Unlike bees, wasps can sting as often as they please using their un-barbed tail-mounted weapon. The sting contains an alkaline form of venom, unlike bee stings which are acidic. This is the supposed logic behind our mothers putting bicarbonate of soda on bee stings and vinegar on wasp stings. In my mind, the hot-poker pain of a wasp sting is forever associated with the pungent smell of the vinegar my mother used. It was never effective as far as I could tell.

Once, on holiday at a villa in Umbria, I was stung by a hornet, the splendidly-named Vespa crabro, a much larger relative of the wasp. I was relaxing on my back on a Li-Lo in the swimming pool, contemplating the evening sky after a hot day driving around southern Tuscany. Paddling myself about I managed to trap a floating hornet between my upper arm and the side of the Li-Lo. The hornet, already distressed by its imminent death by drowning, stung me immediately. The pain was intense and persistent and a large indurated area developed around it which lasted for days.

Apivorus means ‘bee-eater’ but the European honey buzzard (Pernis apivorus) eats far more wasps than bees and is actually called the Wespenbussard in German. It’s not even a true buzzard as in the familiar Buteo group. Honey buzzards are secretive summer migrants and mainly breed in central and southern Britain. There are several breeding pairs in Scotland too but you are very unlikely to see them. Birds perch in mid-canopy to scout for prey. The claws are blunt for a raptor – rather like a vulture’s – and it uses its powerful feet to excavate wasps nests from burrows to get at the grubs. It has dense scaly feathers over its face to protect it from attack and the feathers are thought to contain a wasp repellant. The European bee-eater (Merops apiaster) also eats a lot of wasps. It is adept at knocking out the stings of bees and wasps on its perch before consumption.

Adult worker wasps are female and only live for an average of 2 weeks. Once the queen has begun the nest and produced the first few workers she becomes flightless and confines her activities to egg-laying. The workers are actually capable of laying haploid eggs that produce male wasps. The workers feed the larva on masticated caterpillars and aphids. In return, the larvae secrete a sugar-rich fluid which is the main food of the workers who cannot digest solid food. The colony expands to a maximum of about 10,000 individuals.

At the end of summer, sexual larvae, queens and drones, are produced which will mate before the queens seek out their winter quarters. When these sexual forms pupate the supply of sugary secretions runs out and the workers start looking for alternative sources of energy from any unharvested fruit such as plums and figs – or from picnics. The old queen dies and the social structure of the nest disintegrates. The workers start to succumb to starvation and cold and this is the time of year when we must beware the groggy, moribund Jaspers who still pack a punch.