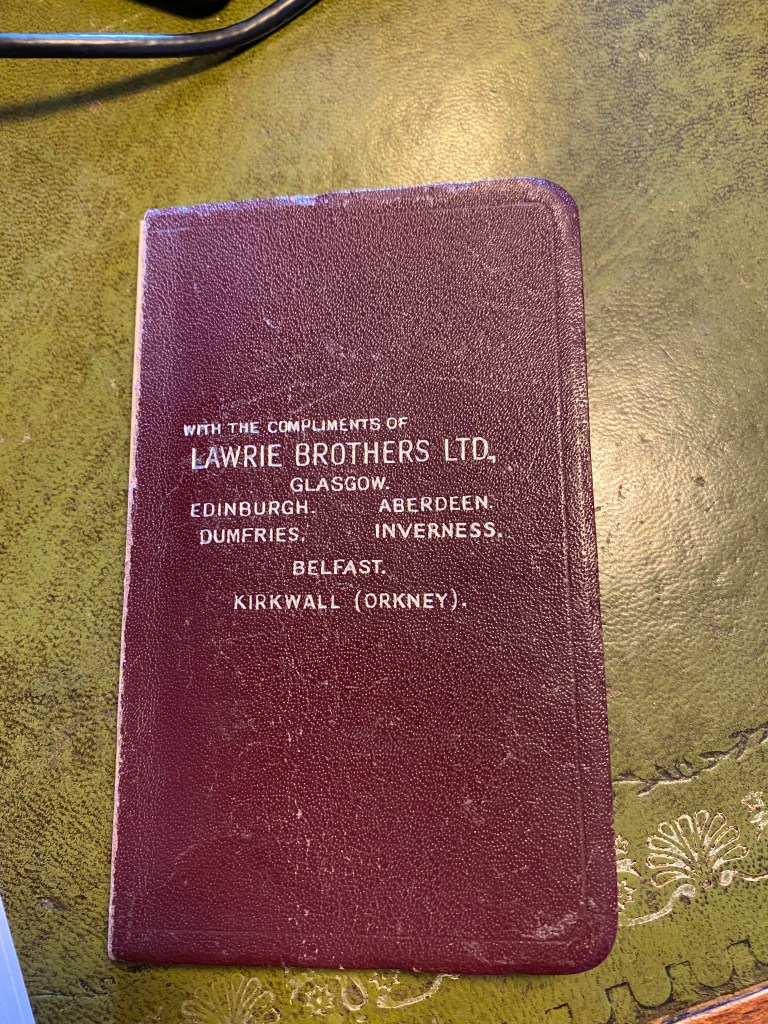

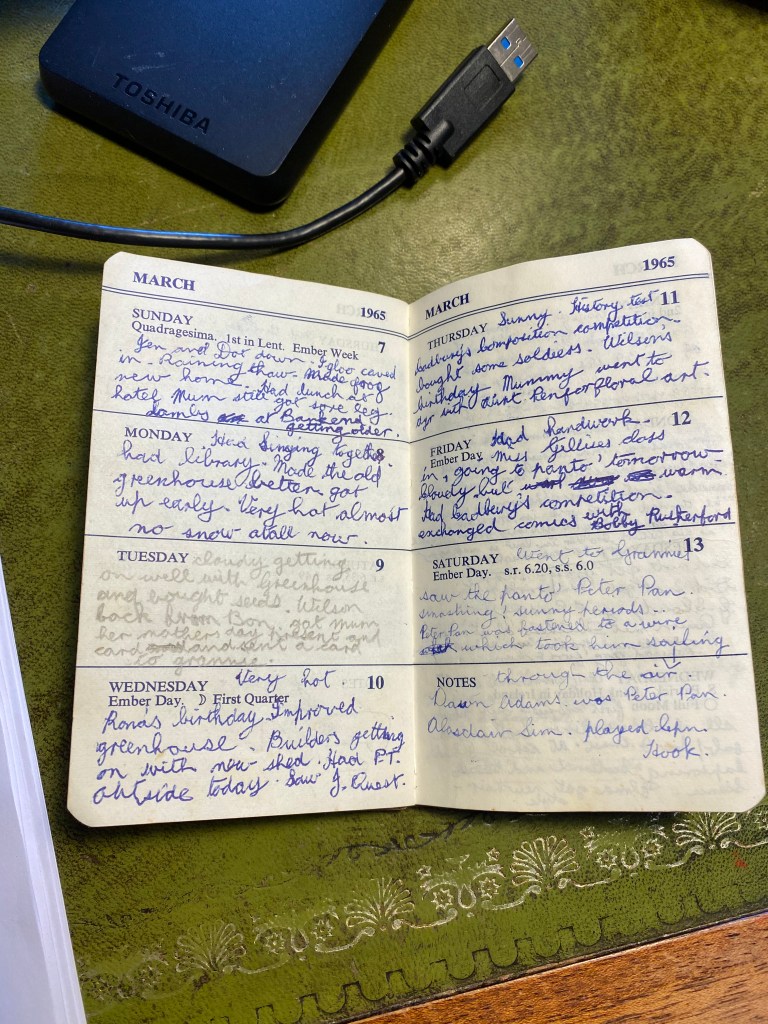

When a colleague learned I kept a diary he asked, ‘What do you write in it? Cornflakes again today?’ ‘No’, I said, ‘It’s all about you actually!’ That wasn’t too far from the truth at the time – but why keep a journal at all unless you are Pepys, Boswell or Chips Channon? I kept one intermittently as a child, as do most people. Recently I transcribed my 11-year-old experiences from 1965. For their entertainment I sent it to a friend who had shared many of those events.

‘Smashing’ panto – Alastair Sim played Captain Hook

My diary-keeping stuttered on into the Seventies. I kept a record of a secondary school trip to Norway for the amusement of my fellow travellers. I also have a complete diary for 1973 and a chunk of 1974 straddling years one and two of medical school. The rest of university was a shameful chaos and mercifully went unrecorded.

I did try to keep journals of holidays on the basis that these would be more interesting than the quotidian routine, but they are mostly incomplete. As soon as matters became enjoyably complicated the logging of events tended to lapse. Frustratingly, my account of a 1977 student elective in New York stops after three weeks with six more action-packed weeks to go. In any case, the quotidian is not necessarily less interesting than foreign jaunts.

One’s distant, undocumented, memories get hauled out randomly at dinner parties, over drinks in the pub or just for the contemplation of that inner eye that is the bliss of solitude. They are then put away again, on each occasion having mutated slightly towards your preferred version of the past. Eventually they can become complete fabrications. I have heard junior colleagues quote me using words I know I would never have used. Their pleasure in this false recollection makes it difficult to contradict them.

Even further back, my brothers and I have incompatible recollections of many shared childhood events. Some of this is simply differences in what an individual chooses to retain, but often there is a conflicting version of the raw facts of the matter. History is written by the victors of course and I feel a diarist need only be true to himself. The experiences of others around you can only be inferred. Diaries are inevitably more valuable as insights into the author’s personality than as sources of hard historical truth – but at least a contemporary written account has the chance of reflecting the truth better than a disembodied anecdote regurgitated decades later.

My earliest attempts at making a record have proved quite disturbing to read. Apart from the inevitable cringe factor, scenes are depicted of which I have absolutely no recollection. Names appear, confidently written, of people I cannot now recall. Even worse, I have discretely used initials to represent some of them making identification even less likely. I had assumed that all my memories would revive if prompted by the written word – but they don’t. Some things are stubbornly locked in the past and no amount of CPR can resuscitate them.

In my early thirties life became more settled. At the time I was thinking about writing fiction and wanted to base that on experience. The problem is I never shook off my conviction that history and biography are more interesting than made-up stuff. I could see that writing fiction releases you from the yoke of facts, perhaps allowing a greater truth to be portrayed. I decided to make a record of life, work and people as fodder for some future creative process as yet unspecified. Very soon it became an obsessional end in itself. 34 years and millions of words later I’m still gathering information.

A scriptwriter friend of mine expressed scepticism that I could have sustained this effort for that length of time and demanded proof. I fetched 2008 from the shelf as that was the year we travelled to Australia to visit him. I opened it at the page describing our arrival in Sydney. ‘You won’t be able to read it anyway, my handwriting is appalling,’ I said handing it over. ‘On the contrary,’ he said, ‘I can read it perfectly well.’ He asked how many words I thought the diaries represented. As a proper writer who earns his living by words, logo-metrics are of interest to him. After a quick count to derive the average number of words-per-page we calculated the total stood at approximately 5 million. ‘That’s a hundred film scripts!’ he said.

Mindlessly, I have recorded everything without prejudice. Cornflakes, jokes, anecdotes, births, deaths, rites of passage, children’s first words, sickness, all the striking or mundane events of life and work. I take my diary everywhere with me. After all, one should always have something sensational to read on the train.

My diaries as they stand are more a set of lecture notes than deathless prose. I assumed the narrative could be filled out later to make it readable. Having done that a couple of times for smaller projects I discovered that this process more than doubles the volume of verbiage. Even with incomplete and unreliable recall the dried-out facts expand dramatically when hydrated by grammar and a few adjectives.

But no matter how recently the pen has crossed the paper there remains the question of veracity. Even recording current events more or less as they occur, the moment you write something down you impart a self-flattering spin to it. A diary is always subjective, never objective. One of my favourite diarists, Jeremy Clarke who writes ‘Low Life’ for the Spectator, says of his partner:

I would like to say much more about her only she forensically analyses every mention I might make of her in these columns and measures it against something she calls ‘truth’.

What then should be done with this unreliable archive and the thousands of hours of pointless effort it represents? My wife’s grandfather’s World War I experiences were consigned to the fire by his widow. Perhaps a bonfire of the vanity project is what is called for.

For contrasting journal-keeping techniques I would recommend:

Hugh Johnson on Gardening The best of Tradescant’s Diary

Jeremy Clarke Low Life: The Spectator Columns