‘The child is father of the man,’ said Wordsworth in My Heart Leaps Up. Once, when I was very young, my grandmother complained of feeling unwell and I apparently said, ‘You can tell me about it Granny, I know all about anatomy.’ A certain amount of self-confidence is helpful in a medical career.

Brought up on a farm, I became interested in the structure of living things. At first I drew animals, then later, the human body. At the Highland Show I discovered a book on avian biology. I shot and dissected birds to see what was inside them and tried to match my findings to the diagrams in the book. I also tried to identify the internal organs of fish when I gutted them. Like a teenage haruspex, I read entrails and pondered my future. It was all a bit Jeffrey Dahmer, according to my daughter.

The ‘large practice’ veterinary surgeon who attended our farm was impressive. He had a silver Mk2 Jaguar with in-car radio communications when that sort of thing was practically unheard of. The boot of his car was crammed with interesting equipment and drugs. Our head byre-man, Richard, was a fan. He was of the opinion that doctors could simply ‘bury’ their mistakes, but the loss of a valuable pedigree animal was a much more serious – and conspicuous – matter. At that age I missed his implication that the relationship between an NHS doctor and his patient was subtly different from that of a costly veterinary surgeon and his client. Richard told me our vet knew more about cattle than the local GP did about people, and I believed him.

In the small ‘office’ at the head of the byre was a cupboard containing some rudimentary veterinary equipment for the stockman and DIY vet. There was a vicious-looking trocar and cannula for stabbing cattle suffering from ‘bloat.’ This is a a life-threatening condition caused by a gas-distended stomach. Having entered the stomach through the cow’s flank, the trocar was removed allowing the gas to escape through the cannula. I never saw it used in anger.

There were large bottles of magnesium solution which were administered to cows with ‘grass staggers’. You gave the fluid through a long rubber tube via a fearsome large-bore needle. The subcutaneous infusion created a blister under the skin that had to be massaged to make it disperse. I was intrigued that you could intervene in a crisis and restore equilibrium.

Sometimes I got to observe the vet at work. I saw him use a metal detector to confirm that a cow had swallowed a foreign body. It turned out to be a piece of barbed wire. He fished about inside the animal and removed it. I saw him correct a ‘twisted stomach,’ more properly called a volvulus. This is when part of the gut rotates around its point of origin, cutting off the blood supply to the affected segment. In due course, if untreated, the piece of gut dies and so does the animal. Surprisingly, the cow remained upright in a loose box throughout the whole procedure. The vet injected local anaesthetic on each side of the cow’s spine then cut two large incisions below the pin bones, part of the pelvis. There was partial paralysis of the back legs and it was my job, along with Richard the byre-man, to keep the cow upright.

Normally, a cow’s hide closely follows the contours of its bones and soft tissues, but cutting into the abdominal cavity results in the skin pulling tight between adjacent bony prominences. Air is then sucked into the abdominal cavity. It was a cold winter day and as the cow breathed, clouds of condensation puffed out of the incisions and blood trickled down her flanks.

The vet worked from both sides, successfully untwisting the stomach. He then anchored it in place with stitches and sewed up the layers of peritoneum, muscle and hide in turn. The cow survived and the whole procedure made a big impression on me. However, I had my eye on an urban job and never seriously considered applying for vet school. My mother’s relentless campaigning had steered me away from other careers and I was duly accepted to study medicine at Edinburgh. I calculated that if I didn’t like it, I could always drop out and do something else with less demanding entry requirements.

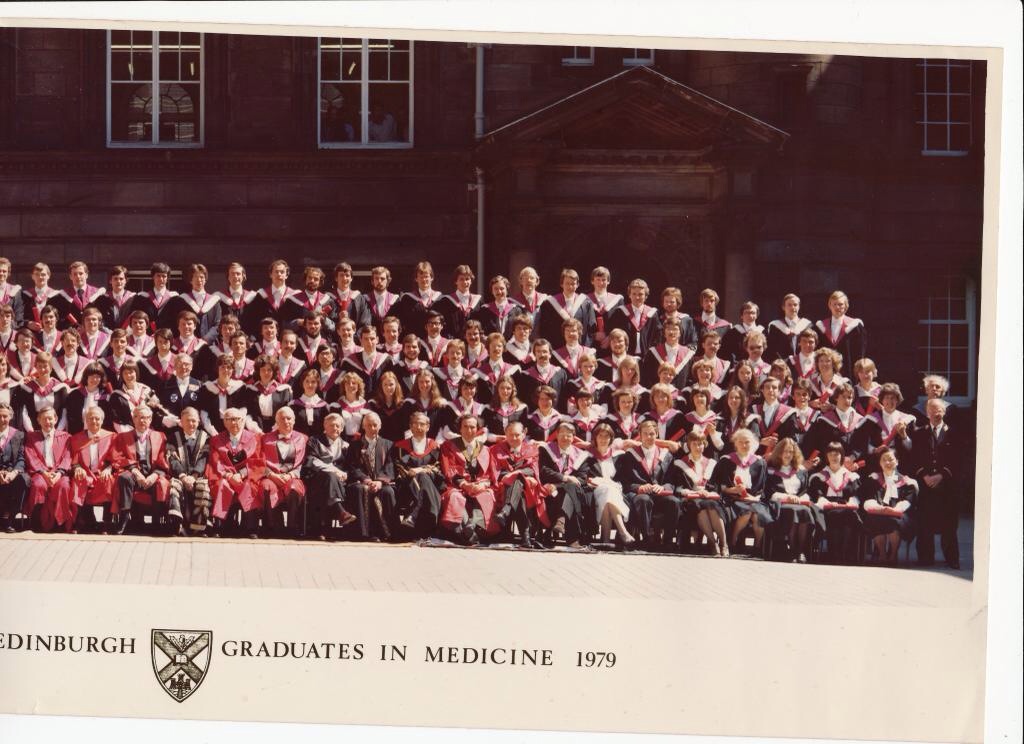

The magnificent purpose-built Italianate Medical School of Edinburgh University (1880) was meticulously designed by Sir Robert Rowand Anderson after an extensive European fact-finding tour. The building abuts the McEwan Graduation Hall. It encloses a large central quadrangle called the New Quad and is accessed by archways. It features lanterns on cast-iron supports. My eventual graduation photo, seven years later, was taken in that courtyard.

In the eastern corner (just to the right of the photograph below) is an archway that led to Bristo Square and the Teviot Row Student Union. Next to that archway was the door to the Medical Faculty Office or ‘Fac Off’ as the students referred to it. The Fac Off was on the ground floor. The Anatomy Department was upstairs.

With the benefit of decent English A-Levels you might be allowed to enter directly into second year at Edinburgh, but with Scottish Highers you had to complete the full six-year course. First year was all basic sciences: physics, chemistry, organic chemistry, biology and labs so during Freshers Week, to make us feel more medical, we were given a rudimentary course in first aid. People would expect us to know something about res medica from now on.

In small groups we had tours of the medical school conducted by a fourth-year student. The one who took us was short with curly red hair and sideburns. He was dressed in a tweed jacket and grey flannel trousers. He looked like someone’s grandad. He took us to view the legendary Anatomy Lecture Theatre, modelled on the one in Padua where Vesalius had taught. In Second Year we would have 9 a.m. lectures there every day, perched on the precipitous banks of seats. Side stairs emerged half way up the auditorium seating allowing latecomers to slip in. One day, I would give my last lecture in that theatre.

We were taken to see the Anatomy Museum, with its two elephant skeletons flanking the entrance and were shown the copy of Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp which hung on the wall nearby. Finally, we were conducted up more stairs to the dissection room. The pungent fumes of formalin became more intrusive as we ascended. In the stairwell hung posters illustrating great moments in medicine, including a painting of Charcot teaching at the Salpêtrière.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Clinical_Lesson_at_the_Salpêtrière

For obvious reasons the dissection room had no outward-facing windows but it was brightly lit from above by a glazed sawtooth steel roof. Down either side of this very large room were rows of trolleys bearing objects draped in grey tarpaulins. Our tweedy guide was approaching the climax of his performance. ‘And these,’ he announced, ‘Are the bodies!’ With that, he threw back the nearest drape to reveal two sickeningly white feet inside a thick polythene bag with a puddle of formalin gathered under the heels. The girl next to me promptly fainted and our tour turned into a practical.

In Second Year, boring basic sciences completed, we finally made it back to the Anatomy Department. I liked studying anatomy. After all, as Pope said, ‘The proper study of mankind is man.’ Six of us were allocated to each body, three to a side. As with all our practicals we were sorted alphabetically. I got to know fellow students, Stewart and Sternberg.

We bought our Cunningham’s Dissection Manuals from Donald Ferrier’s Medical Book Shop in Teviot Place and watched, fascinated, as they were expertly covered in the trademark green paper and white labels. At the 9 a.m. lectures our teachers attempted to emulate the great D J Cunningham by building up chalk drawings of bone, muscle, nerves and blood vessels on the blackboards. Anatomical posters hung on the walls.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_John_Cunningham

Upstairs we dissected the morning away, while consulting the relevant sections of our manuals: upper and lower limb; thorax; abdominal cavity; head and neck. Afterwards we walked under the archway in the quad and through the gates next to the McEwan Hall to the Teviot Row Union for lunch. Human grease spots marked the green covers of our manuals. We discussed our progress over haggis and chips and a yoghurt. For no extra charge you could enjoy waitress service (of the same refectory menu) upstairs in the dining room. Many of our lecturers ate there too. There was a bronze bust of Churchill in an alcove at one end. After lunch it was essential to have a refreshment in the ‘upstairs bar’. Each bar in the Union had its distinctive clientele. I liked the old-fashioned smoky atmosphere in the upstairs bar, which featured a piano. Playing that instrument brought chances to meet students from other faculties, especially musicians.

In the end I did seven years at university because I had to repeat third year. Throughout my first attempt at year three, I rose at midday, had breakfast in a local café, then went to a snooker club in Morningside my flatmate and I had joined. For two terms, I essentially did nothing but sleep and play snooker. In March I celebrated my 21st birthday. At the end of the three term academic year I had no notes to read, having attended just three lectures in total. The other students needed their notes for themselves and in any case, lecture notes are very individual things. What gets recorded – and whether anyone else can read it – is unpredictable. It was too late for me to read the bulky textbooks that covered the course and so I ended up with resits.

During that summer of studious penitence my father became gravely ill with pancreatitis. He collapsed at the Ayr market while buying cattle. He ran a large family business and when he became ill our lives were plunged into chaos. After several weeks in hospital, he died, just before my exams. With his high profile in Scottish agriculture, a big funeral followed. As eldest son, I took cord number one at the graveside. Three days later I had my resits, exactly a week after Dad died.

I managed to pass those subjects I’d already studied; the more appealing Pathological Sciences. I completely ploughed Physiological Sciences which I hadn’t even touched. Under the circumstances, I was allowed to repeat my third year doing only those subjects I’d failed. This gave me time to play a lot more snooker and meet a new set of interesting classmates in my new year group.

As a postgraduate I finally picked up my game, became a medical registrar and passed the examination for membership of the Royal College of Physcians (MRCP). This is the main qualification for a career in general medicine. At that time, to progress further, you also needed to study for an MD or PhD and preferably get a ‘BTA’ (Been To America). Even when extensively post-nominalled, you had little control over where your Senior Registrar post might be. If I really wanted to stay in my adopted city I needed to change lanes into another specialty. Since schooldays, I had toyed with a career in Psychiatry. This was because I imagined it might combine science and the arts. One of my consultants in general medicine advised me against it. ‘I don’t know exactly what the future holds, Allan, but it will involve those big new machines in radiology. I think that would suit you.’ Not ready for a specialty that didn’t ‘hold beds’, I ignored him.

During the interview for entry to the Edinburgh training scheme in Psychiatry I was asked if any of my family were medical. I said no. They then asked what had first attracted me to Psychiatry. I answered, truthfully, that I had been fascinated by the portrayal of psychiatrists in films and television as brilliant insightful analysts of the human condition. Emboldened, I mentioned Gregory Peck in Spellbound. This seemed to go down well, and I was in.

In spite of my theory about it combining the arts and sciences, I was unhappy from day one. There were two rival psychiatric camps in the 1980s. I was immediately identified as an alien by those of my contemporaries who had entered the specialty solely to conduct psychotherapy. To compound my sins, my car was bad. ‘When we saw your car we thought, “Here comes the medical model,” ‘ one of them remarked. I hadn’t bargained for all this political infighting. I told friends that if you wished someone ‘good morning’ at the Royal Edinburgh Hospital, you would be asked what you meant by it.

My new boss, the professor of psychiatry, had once been a neurologist. He would later become Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at Edinburgh and President of the Royal College of Psychiatry. Unlike the psychotherapy gang, he was keen to have an MRCP on the books. The topic of his inaugural address was whether or not you needed to be a doctor to practise psychiatry. He felt that if you were dealing with the major psychoses or the degenerative brain diseases and were administering powerful drugs, you did need to be a doctor. Otherwise, not so much.

As the year wore on, I found myself swamped by outpatients, some of whom threatened suicide when I hinted they might be well enough for discharge (which they were). When I asked for advice about this mess I was told I was ‘encouraging dependency’. Despite these problems the trainees were left almost completely unsupervised by the senior staff. I became increasingly annoyed and disillusioned by it.

On call, we first year trainees, only a few weeks into the job, were told to offer short term psychotherapy to patients, some of whose notes were so thick they had clearly seen every consultant psychiatrist in Edinburgh. In a lecture on psychotherapy, given by another illustrious professor, I questioned the value of this to our patients or us as trainees. He told me, ‘If you said that to me in an examination I would fail you and trust you would take up some other branch of medicine.’ This seemed to be a clear indication of how I should proceed. The following week a consultant from my own ward took me aside and told me that what this professor had said to me in the lecture would have no influence on my future career. I resolved that it wouldn’t. I was miserable and it was contaminating my private life.

Having turned into this blind alley, I had to escape. In the end I stuck it out for a full academic year but half way through, when the radiology posts were advertised after Christmas, I applied. My ex-neurologist prof, who liked me, called me over to his office in the ivory tower to explain myself. He placed me in a low armchair then perched on his desk, looming over me. He opened with, ‘Why are you leaving?’ I answered truthfully that I’d found no satisfaction in the job. I felt that the patients got better or worse unconnected with anything I did for them. ‘What interests you in medicine?’ he asked. I found myself saying I liked structure and function. He smiled, ‘We could be 100 years away from that in psychiatry.’ He then ended the interview amicably and told me to let him know how I got on.

Towards the end of those 12 months I gave a talk to the hospital grand rounds on the madness of George III. Sitting at the back of the lecture theatre, and bored during someone else’s talk, I started reading the profusion of graffiti inscribed into the wooden desktops. There were lots of initials and dates. Rashly, I wrote ‘PSYCHIATRY IS BUNK – AJMS 1983-84.’

The radiology interviews were tricky. I now seemed to be someone who had no idea where his career was going, and worse, had even been a psychiatrist. It seemed I would be a unique specimen within radiology. A rival colleague waiting for her interview claimed to have heard them discussing me in predictably negative terms. Despite this, they appointed me, but it was a strong field and I was the oldest and least qualified of the four of us. The others all had MRCP and published research.

When I announced my radiology appointment to my psychiatrist chums there was a degree of ill-disguised animus. I was told, ‘Radiologists are like mushrooms. You keep them in the dark and feed them bullshit.’ Another said, ‘When we looked at X-Ray reports, one of my old consultants used to say, “Don’t read that laddie, it wasn’t written by a real doctor.” ‘ Top humour, all of it.

Perhaps because it did indeed suit me or maybe because I was finally escaping from psychiatry, I loved radiology from the outset. It was a return to the study of the undisputed structural aspects of humankind; the plumbing and wiring. It was also an enjoyable intellectual challenge to absorb all that information and develop new diagnostic skills. Feeling very positive about life, and mindful of what he had said, I wrote to my old psychiatry professor, the future Dean of the Faculty of Medicine. , telling him I was happy and thanking him for his advice.

He wrote back:

Dear Allan

I do hope you settle down in your chosen speciality soon. Should you have any doubts about your decision, I suggest you recall what you inscribed on one of our lecture theatre desks not more than six months ago: ‘PSYCHIATRY IS BUNK – AJMS 1983-84.’ I trust this was an accurate reflection of your feelings at the time.

Yours,

REK

All things must pass and the old medical school is now the home of the History Department and other Edinburgh University odds and ends. Clearly it was no longer ‘fit for purpose’ but I count it a great privilege to have attended lectures in the quad, then crossed Middle Meadow Walk to the wards of the Royal Infirmary. This experience is no longer available to Edinburgh medics. The wonderful building that was the Royal Infirmary on Lauriston Place, is now undergoing a seemingly endless conversion to apartments, offices and restaurants. The famed surgical corridor with its checkerboard floor of ‘plantation rubber’, its marble busts and the names of donors in gold lettering on the walls, is to become the new Edinburgh University Business School.