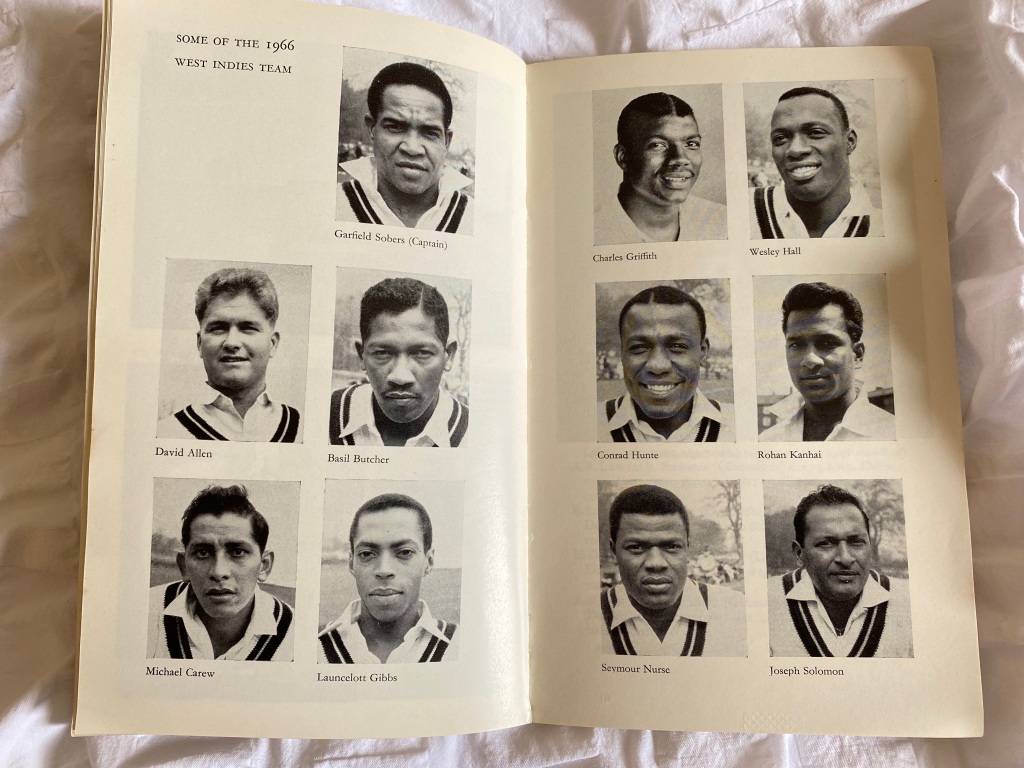

I have no idea where my affection for cricket came from. I have always found it easier to hit balls with a bat or a racquet than to kick them, so maybe that’s the reason. Cricket is played by more people in Scotland than play rugby – but obviously both have always been less popular than football. There are localised hot spots in the far north east around the Moray Firth and the more expected, Fife, Lothian and Borders. On my side of the country there was something called the Western League. Like rugby, my introduction to the sport was on BBC black-and-white TV broadcasts in the 1960s. I’m sure England were playing test matches against other countries, but it was the West Indies that dominated my imagination and now, my memory.

England had Geoff Boycott, Colin Cowdrey, John Edrich, Ted Dexter, Tom Graveney, Ken Barrington, John Snow, Derek Underwood and Ray Illingworth; but the West Indies had Wes Hall, Charlie Griffith, Lance Gibbs, Clive Lloyd – and Garfield Sobers. Lloyd and Sobers were my heroes. Lloyd for his astonishing cover fielding and Sobers for everything. I even turned up my collar and tried imitating his bowling style. Hall and Griffiths had murderous pace and I can remember the Charlie Griffith bouncer that felled ‘Deadly’ Derek Underwood on his debut and left him with a large haematoma on his forehead. It seemed shockingly unsportsmanlike at the time.

At secondary school I finally got to play. The standard of kit was appalling, consisting of ancient bats and pads in disintegrating bags. The balls were scuffed into complete anonymity. We were coached by Mr Moffat, who was South African, and later Mr Steinlett who was English. Both of them had played at quite a high level and the team owed its existence to their enthusiasm and commitment.

Mr Moffat taught English and was balding, cerebral and Christian. We seemed terrible unrefined compared to him. Harry Kirkwood, the class’s roughest diamond, enjoyed chewing gum during lessons. ‘Harry! Are you masticating?’ asked Mr Moffat. Harry, bewildered, glanced down at his lap. ‘Me sir? No sir.’

Mr Steinlett was more worldly wise and droll and had played cricket in leagues in the north of England. ‘I once bit myself on the arse, Stevenson,’ he told me as we were preparing for the teachers versus pupils match. As he expected, I was intrigued. ‘OK, how did that happen?’ I asked. Having hooked his fish, he replied, ‘I have a partial denture and I put it in my back pocket for safety during a match. I was fielding at long on and the batsman went for a six. I was back-pedalling to catch it, tripped over the boundary rope and landed on my backside.’

Our pitches were terrible. They were used heavily for football during the winter and the school had nothing resembling a cricket groundsman to effect any kind of repairs for the summer game. The bounce was unplayable, in fact dangerous, and we were reduced to playing all our official matches away from home. The contrast with teams like Ayr Academy, who had a beautiful ground at Doonfoot and were coached by a West Indian professional, was embarrassing. We didn’t even have proper whites or, occasionally, enough willing participants to make up a full eleven. The carpet-like perfection of Ayr’s pitch was a wonder.

The school ran a first and second year team, but from third year onwards there were just first and second elevens to play for. Due to my enthusiasm rather than any ability, I was captain in first and second year. Our abysmal record was the subject of amusement and some derision at school. In the bus on the way home from matches my own team would sing, ‘We want Stevie with a rope around his neck and six feet off the ground!’

Still, we did our best and it soon became clear that cricket was not a game for softies. A cricket ball weighs nearly 6oz and travels at over 100mph when struck. After being hit in the face during a practice, one of our team sustained a detached retina and never came back. During one match, hoping for a catch, I moved our best batsman to short leg. The intended victim promptly smashed one straight onto his knee cap. Our man was carried off. As an enthusiast I was drafted into the first eleven from third year onwards despite being 3 years younger than most of the team. In my fist season we played Kilmarnock Academy. One of their sixth year boys was already playing with seniors in the Western League .

I was simply making up the numbers at this stage, filling unimportant fielding positions and going out to bat well down the order. The Western League boy was bowling when I reached the crease. He was a huge mesomorphic redhead with a hairy chest visible through his partly-undone shirt. I’d never seen anyone take such a long run-up before. He marched off towards the sight screen furiously polishing the ball as I took my guard. ‘Middle and leg please,’ I said in a faint voice. ‘That is,’ said the umpire. The ginger monster turned at his mark and came charging in.

If you’ve never played cricket you will be unaware that the seam on the ball makes a faint noise as it spins. The delivery was travelling so fast I was completely unable to see the thing – but I could hear it buzz past. I made a vague gesture at where I thought it might be, made no contact, and heard it smack into the wicket keeper’s gloves an instant later. All the close fielders ooh-ed and ah-ed to let me know what a close call I’d had. The second delivery went the same way. The third was short and reared up striking me a glancing blow on my right cheek. Later, a bruise came up bearing the imprint of the stitching on the seam. By this time I was in fear of my life. Needless to say in 1969 we wore no helmets. The fourth delivery was a blessed relief. It pitched on a length, went through the gap, and stumps and bails flew in all directions. The close fielders roared their approval and I trudged back to the pavilion wondering if it would be sensible to give up cricket.

Later that season we played Ayr Academy. Again, I was filling gaps in the field and the batting order. The captain put me at square leg just forward of the umpire. The Ayr captain was having a great knock. Suddenly, he smote one on the leg side about six feet off the deck. These things are purely a matter of reaction, and with no time to think, I flew to my right and caught the ball in mid air at full stretch, landing face-down at the umpire’s feet. He signalled that the batsman was out.

My batting contribution that day was another duck and I was a bit down at the post-match cup of tea in Belleisle Park’s imposing mansion house hotel. ‘Never mind,’ said our coach. ‘Today you took a catch you’ll remember for the rest of your days.’

Eventually in sixth year I captained the firsts – such as we were. My batting continued to disappoint but I was a reasonable medium pace bowler. Against Kilmarnock that year I was getting the treatment from their number four and became very frustrated. In desperation I bowled him a full toss. He attempted a hook, but mis-timed it and the half-struck ball came straight back at me for a catch. My momentary joy was dispelled as the ball struck me right on the end of my left index finger and I dropped him. The finger rapidly swelled up into a purple sausage.

I thought I wouldn’t be able to bat, but Kilmarnock went through our order very quickly and I gingerly pulled on my gloves and went out. I wasn’t able to grip the handle firmly with my injured hand. The first delivery reared up and struck me directly on my fat blue finger. The pain was exquisite. Not a game for softies.

I alluded to George Burley (footballer: Ipswich and Scotland) in my piece on rugby. He was two years younger than me and an age group international footballer. In the summer term of my sixth year he decided he wanted to have a go at cricket and turned up for a net in the gymnasium. By this time I felt I could bowl a bit and was skeptical that a complete novice could be competent against an experienced bowler. George picked up the bat and asked me if he was holding it properly. I said yes, he was. He then took up a very professional-looking stance and gazed back at me at the bowler’s end. I began bowling at him as fast and as accurately as I could. With effortless ease he smashed every ball away as if I was sending down underarm lobs at beach cricket. Great sportsmen can turn their hand to anything and are literally in a different league from the also-rans.

My best innings ever was against the teachers – 26 not-out I believe. That match was held at the end of summer term when our meagre numbers had dwindled and some of my batting partners had had to go in twice. I never played again apart from one scratch student match on the Meadows. I clean-bowled my opponent on the first delivery with a full-toss, but the others said that wasn’t fair and he should stay at the wicket. I was told not to bowl any more balls like that.

In 1975 I travelled to Glasgow to see Cowdrey and Denness play at West of Scotland in a benefit for Salahudin. Intikhab Alam, Majid Khan, Asif Iqbal – and Sir Garfield Sobers were also playing. It’s the only time I’ve watched First Class cricketers in action. It was a lovely day and the crowd were excited to see the ageing Cowdrey in action. By this time he was noticeably portly. Acknowledging his warm reception, he cheerfully took his stance and began clipping every delivery to the boundary in an exhibition of matchless class. He needed the merest gesture towards the ball to send it flying to the ropes. What a great sport it is when an overweight forty-something can play like that at the highest level!

In 1981 I was a medical registrar in Dunfermline when Ian Botham (assisted by Gatting, Gower and Willis) had his miracle test series against Australia and the combined attack of Lawson (briefly) and Lillee. We watched as much as we could on the mess TV between clinics, eating and getting bleeped. Botham rescued the series when England were 0-1 down and his ability to swat bouncers over the boundary, seemingly without looking, was astonishing.

After that, my interest in cricket waned and I lost touch with the sport, but the smell of cut grass or linseed oil brings it all back. I don’t think the shortened game is very appealing, aimed as it is at people with a short attention span and no appreciation of the subtleties of a sporting engagement that can last five days.

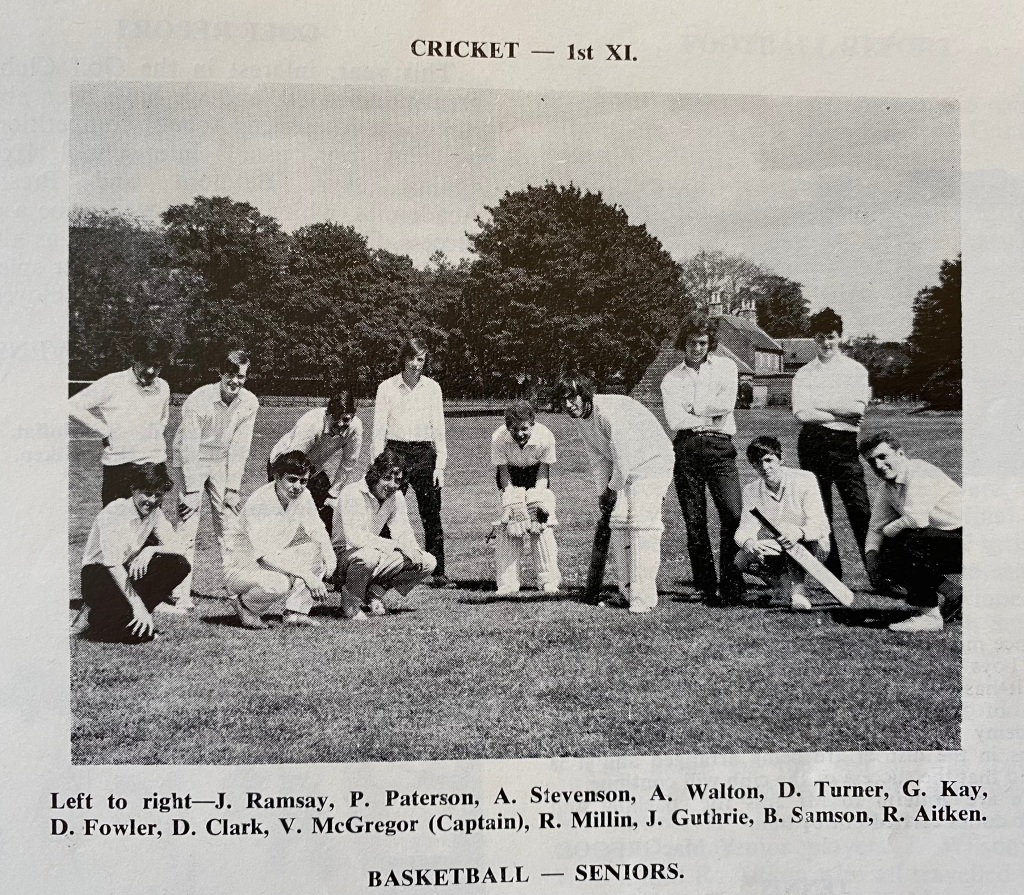

The First XI in 1970 when I was 16