In 1977 I went to New York to do a six-week student elective in gastroenterology at New York University. I arrived in the middle of a heatwave. The blackout that year had resulted in widespread looting; the Bronx was ‘burning’ due to insurance fires; the police were on strike and picketing the Brooklyn Bridge and David ‘Son of Sam’ Berkowitz, the .44 caliber killer, was shooting courting couples at random. His arrest for an unpaid parking ticket was imminent.

The placement was at Bellevue Hospital, a name forever associated with the notorious psychiatric wards. In fact Bellevue was also a general hospital housed then in an enormous brutalist block known as ‘The Cube’. The original infamous Bellevue building next door was being demolished while I was there but I managed to get into it and wander the deserted corridors looking for ghosts. When I heard some raucous voices coming from one of the abandoned rooms my courage deserted me. I fled back to the relative safety of the Cube with its handcuffed prisoners and armed police guards.

Bellevue was a public hospital paired with the private University Hospital known as UH. It lies at the east end of 28th Street between 1st Avenue and the FDR Drive. The UN Building is a few blocks to the north. Ward rounds started very early in Bellevue so that the attending physicians (consultants) could make their way along the underground passage from to UH – where the money was. In the UH lobby hung an Andrew Wyeth and a very expensive car showroom was close by. Despite these signs of opulence New York was in severe decline then.

Through an acquaintance with connections in Philadelphia I also spent some time in that city. It was noticeably less crazy than NYC. As a result I met someone who would become a lifelong friend. Al Dorof was living in an apartment on Delancey Place, a gorgeous mid-nineteenth century tree-lined street that has featured as a location in several films including Trading Places. It is amongst the most prestigious addresses in Philadelphia. The fabulous Rosenbach Museum of literary memorabilia is there. Delancey Place has hitching posts and mounting blocks and is older than many of the streets of Edinburgh’s New Town.

The palatial townhouse was divided into flats with a communal kitchen in the basement. Those Philadelphia contacts who introduced me to Al had prevailed on him to put me up for the weekend. We got on very well and I returned to Philadelphia to stay with him when my elective in New York finished. Also staying at Delancey Place was Larry, an acquaintance of Al, who was a radiologist.

One evening Larry came home from the hospital and said, ‘Look what I had to report this morning.’ He propped a frontal skull view against a lampshade and invited us to inspect it. There was a dense round structure projected over the exact centre of the frontal bone (the forehead). Then he showed us the lateral. A faint linear shadow could be seen traversing the skull from front to back, terminating in a triangular metallic structure just above the pituitary fossa. It was an arrowhead mounted on a wooden shaft. Along the line of the shaft tiny fragments of bone and pockets of gas were visible that had been carried in from the entry point. An endotracheal tube was visible in the pharynx indicating the patient was on a ventilator.

‘That is some shot!’ I said, appalled. ‘Well, not exactly,’ said Larry. ‘He was a teenage boy who had an argument with his brother. His brother waited until he was asleep then crept up on him and fired a hunting arrow into his head from point blank range. He made it to hospital but died soon after the radiograph was taken.’ It was the first of many ‘foreign bodies’ I would see on radiographs.

Years after Al and I first met I was on a flight from Philadelphia to Chicago. I had been visiting Al for a week before going on to the RSNA (Radiological Society of North America) conference in Chicago. I found myself sitting in the row behind Larry and made myself known to him. By then I was a consultant in Edinburgh and he was running a large imaging practice in Philadelphia. I reminded him of the skull radiograph and told him this early experience of forensic radiology had ‘stuck in my mind.’

American radiologists in private practice would attend the RSNA with a cheque book in the back pocket of their jeans ready to buy a CT scanner – or two. They were fêted by the equipment reps and for a week the Chicago restaurants did a roaring trade.

In 1984, seven years after my student elective, I started training as a radiologist. After the rudderless ambiguity of my year in psychiatry it was a relief to enter the precise anatomical world of imaging. The plumbing, wiring and scaffolding of the human body is a philosophy-free zone. Clinical radiology is mostly a diagnostic service used by many different disciplines, but the rise of interventional radiology, in which imaging techniques are used to perform physical treatments rather than diagnosis, has been one of the wonders of modern medicine.

As an ex-physician, the only radiology I had been ‘exposed’ to prior to this were chest X-rays. In the acute care setting I thought I could tell cardiac failure from pneumonia and I’d picked up one or two pneumothoraces (collapsed lungs), one caused by me in the course of inserting a temporary cardiac pacemaker. For this procedure X-Ray screening equipment is required to guide the pacing wire into the heart. This taste of interventional radiology was a portent of things to come.

Before my detour into psychiatry, I sat the physician’s exam known as ‘membership’. We had some tutorials from a locum radiologist. He was getting divorced and had left an academic post down south to work briefly as a locum in Dunfermline. His plain film sessions were a revelation and the unexpected depth and complexity of the specialty were revealed to me. He also showed us his pet films, those bizarre, funny or fascinating ones that aren’t strictly exam material; what I would later call, ‘Barnum and Bailey Radiology’.

I was intrigued. I realised that in the past I had been reliant on the written radiology report without appreciating the skill involved in generating that report. It’s easy to say, ‘Ah, yes,’ when the answer is right in front of you. Later, as a qualified radiologist, I would tell my juniors that the only skills a clinician needed to use a radiology department were reading and writing. Write a request, then read the report.

That kind of inter-specialty badinage was a long way down the line for the four of us who started our training together in 1984. All of us had left advanced registrar posts in general medicine where we had been given a great deal of responsibility, but I was the only one who had swerved into a career cul-de-sac. One of my co-appointees claimed to have heard the committee discussing my chequered CV before she was called in for her interview. As intended, it unsettled me until I heard that I had in fact been successful.

Essentially all four of us had been ‘busted back to private’ in another first-day-at-school experience to add to all the rest a medical career hands out. Worse, we had no radiology skills to offer in our first year, and could not do on-call. This meant we lost the substantial on-call supplement to our salaries. And then there were those exams to sit. These proved much more challenging than we expected. Virtually every specialty has its own distinct radiology associated with it and you needed to have an understanding of how imaging fitted into all those disciplines. We were embarking on a vast game of Radiological Trivial Pursuits. Piles of textbooks awaited us.

Unlike my new trainee colleagues who had come directly from medical specialties I did not miss the lack of beds, wards or status, but my knowledge of the human body had decayed since my days in the anatomy lecture theatre. A trick played on new recruits by our seniors was to ask them to name the eight bones of the carpus (wrist). Simple stuff for a second year medical student learning anatomy but tricky for the five-year postgraduate veteran. This was a ploy by our consultants to sober us up on arrival. We needed to grasp that the terra incognita was vast.

In an echo of first year at medical school we had to learn some Physics to give us an inkling of the science behind the big machines we would be using. We also attended an X-ray photography course run by the big supplier, Kodak. X-ray films are essentially photographs. Two days a week we were full-time postgraduate students. We had matriculation cards and everything. We could use the postgraduate union on Buccleugh Place and bunk off for a swim or a drink if a lecture was cancelled. The other three days of the week we tried to acquire the practicalities, the praxis, of our new trade. After the misery and confusion of my year in psychological medicine it was liberating.

Once, during a wild gale, we were making our way to the postgrad union for lunch. As we were walking along Middle Meadow Walk, which lies between the old Royal Infirmary and the Medical School, a tree blew down. It fell between the leading pair in our group and the other two (which included me) who following on behind. With a noise like gunshot and it crashed onto the path between us seconds after the leading pair had passed it. It is the only time I’ve ever witnessed a tree fall naturally. The chances of being killed by a falling tree are around one in 10 million per year.

Later that same year I was goaded into being interviewed for a feminist programme on Channel Four called Watch The Woman. My girlfriend at the time knew the producer from university. The programme was to be about women in medicine. At first I refused – and was mocked for being a coward. Stung, I finally agreed. The producer decided to interview me on Middle Meadow Walk.

A friendly preliminary chat with the interviewer and crew in a café on Forrest Road suggested they regarded me as a thoroughly decent chap. They even expressed surprise and sympathy to learn that I earned less than they did. The weather was fair and we went out onto Middle Meadow Walk to film the interview. This took place on a bench as pedestrians wandered past. It was my TV debut. One of the crew held up a board covered in foil to reflect the sun onto the shaded side of my face. On the sunny side the baleful black eye of the camera lens stared back at me.

Unlike the gentle enquiries lobbed at me over coffee, I was hit with a barrage of challenging questions regarding how much of an evil misogynist I was. The line was essentially, ‘Have you stopped being a sexist?’ to which any answer would be incriminating. One actual question was, ‘Do you feel threatened by nurses taking over doctors’ roles?’ The lens scrutinised me, the sun reflected off the board into my eyes. I gibbered inanely. ‘Do you resent nurses having prescribing rights?’ asked my tormentor.

Suddenly a voice said, ‘Well, I think we’ve got enough. We’ll do the noddies now.’ I felt like saying, ‘Wait! I haven’t said a word of sense!’ – but it was too late. You need the ‘noddies’ when you only have one video camera. The interviewer remained seated on the bench, while I had to watch from behind the cameraman. The interviewer repeated the questions he had already asked me to an empty seat and ‘nodded’ as if listening to my replies. Later they would splice this footage into my original responses as if there had been two cameras, one on me and the other on my persecutor. I wished I could go again. From then on I had a lot more respect for people such as politicians who answer combative questions in a live interview.

An agonising few months elapsed as I waited to view the finished programme. My girlfriend found this very entertaining. On the fateful night I couldn’t watch. As an alternative to hiding behind the sofa, I sat on the stairs and watched the recording later. In the event they used the only bit of sense I’d come out with, but it was a narrow escape. I didn’t keep the recording.

Plain radiographs – what everyone understands by the term ‘X-ray’ – were the basis of our new calling. These images depend on the natural intrinsic density of human tissues to X-ray photons and because bones are made mainly of calcium, a high atomic weight element, they show up well against the muscles, fat and gas of the rest of the body. We learned to injected iodine-based intravenous contrast media to create an artificial ‘contrast’ between structures containing these iodine compounds and their surroundings. Contrast is rapidly excreted by the kidneys so the renal tracts show up well. Injecting contrast directly into foot veins outlines any clots in the veins of the the calf and above.

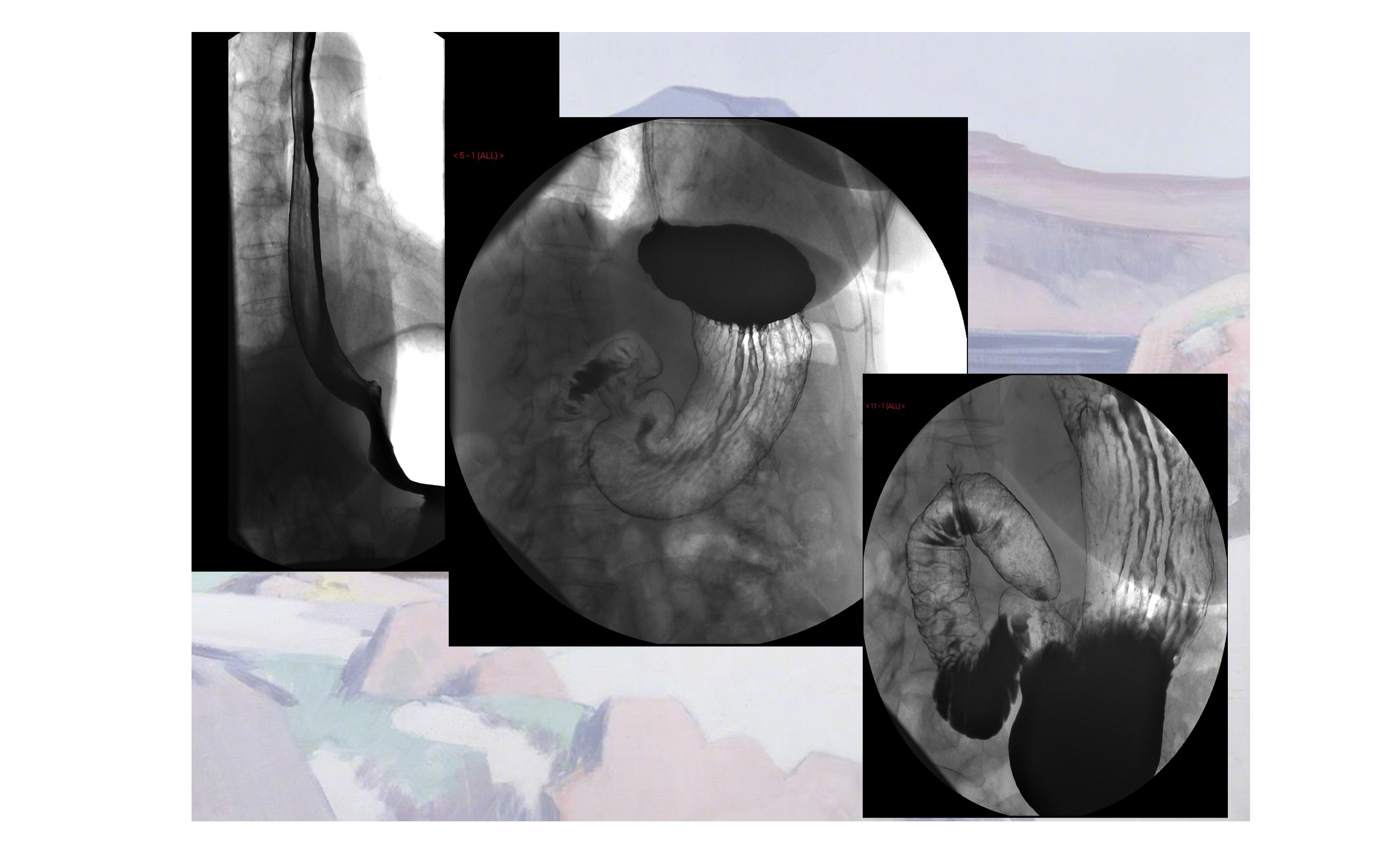

For the gastrointestinal tract we were taught to perform barium studies. Barium sulphate is an inert, extremely heavy compound. ‘Barium’ actually means ‘heavy element’ and it stops X-ray photons in their tracks. You cannot inject it but you can swallow it and it will pass harmlessly through your gut without being absorbed. You can also put it up the other end of the gut as an enema. If you add air or any other gas an exquisite see-through image of the gut known as a ‘double-contrast’ study can be created. I used to liken this to an empty milk bottle with the milk still coating the surface of the glass.

Not all radiography is static. In fluoroscopic screening rooms the tilting examination ‘table’ has an X-ray source beneath it linked to a sensing ‘explorator’ above which can be moved over the patient to follow the progress of the ingested contrast. By pulling a trigger on the explorator, X-rays pass through the patient from beneath the table to strike a fluorescent plate inside the explorator. The image is then intensified electronically and transmitted to a nearby TV monitor. A live, moving radiographic image is seen. This equipment is necessary for dynamic barium studies.

The ritual of these examinations is still embedded in my brain:

‘Turn to your left. Take the cup in your left hand; it’s heavy. Swallow one mouthful for me now please. Now drink the rest as quickly as you can… I’m going to tilt the table down flat… Stay on your left side. Now turn onto your stomach. I’m going to give you a shake; there’s no extra charge for this…’

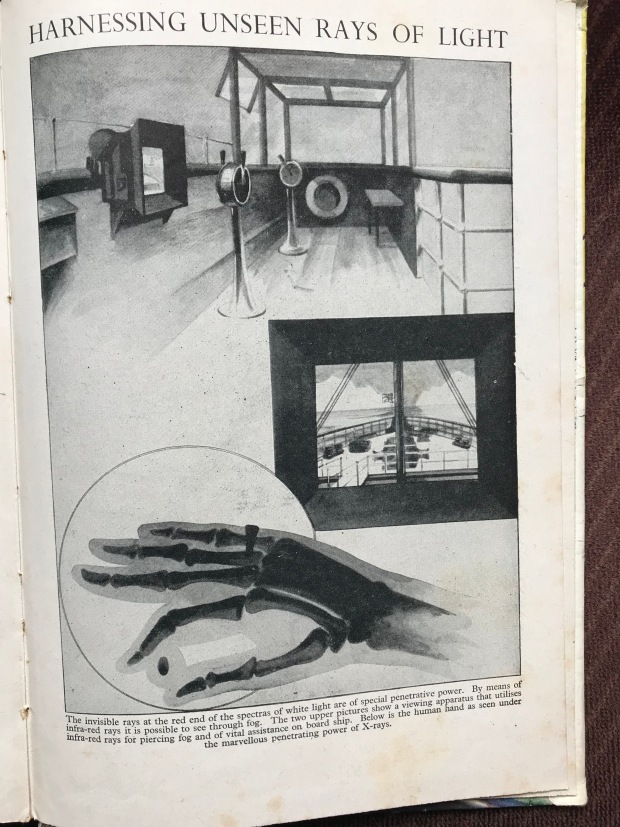

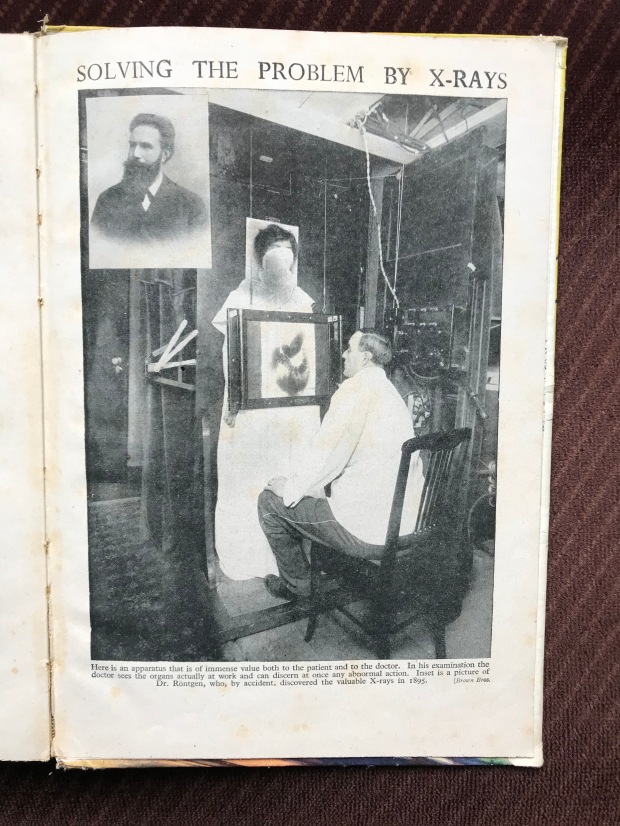

In the ancient photograph below the operator is using direct screening. The X-ray source is behind the patient and the image is produced as the x-rays strike the plate in front of the patient’s abdomen – the operator is in direct line-of-fire. Because the image produced was so faint radiologists had to ‘dark-adapt’ and use their more sensitive night vision. To dark-adapt in advance of a screening list radiologists would don red goggles for 20 minutes. Very little light penetrated these goggles and there were alarming tales of radiologists driving between hospitals while wearing goggles to avoid dark-adapting all over again at their destination.

Our lecturers scared us with tales of the ‘X-Ray Martyrs’ who did not understand the lethal properties of the new miracle rays they were employing. They used their own hands to calibrate the equipment every day – until the bones disintegrated and tumours appeared.

Barium studies have been more or less completely replaced by endoscopy and cross-sectional imaging techniques such as CT and MR. The ability to visualise and biopsy the gut clearly trumps barium, but it took a while for the endoscopists to acquire the resources to deal with the demand. Radiologists who spent their whole careers performing barium examinations and writing great textbooks about it became part of medical history during my working lifetime. Towards the end of my career the occasional request for a barium study in a patient who had declined endoscopy caused panic among our juniors who had no idea how to perform one.

The same fate befell lymphography, a fiendishly difficult technique requiring cannulation of tiny lymphatic ducts in the feet. You injected a blue dye (mixed with local anaesthetic) between toes and, after a while, the dye found its way into the lymphatic ducts which would hopefully show up as faint blue lines under the skin on the top of the feet. You then ‘cut down’ onto them, dissected them out, and inserted a tiny needle into them to inject oily contrast. You hoped you hadn’t found a vein instead. A check X-ray was required to see where the contrast was going. If it was floating around in tiny globules, instead of thread-like ducts, you’d mucked it up.

By the next day the lymphatic contrast would have reached the lymph nodes of the abdomen. Two offset radiographs were taken then placed together on a viewing box. By viewing the films using binocular apparatus a 3-D image of the nodes was produced. You then inspected the nodes for any defects that might represent tumour deposits. This technique was completely replaced by CT. These changes in practice brought no savings to radiology budgets as the growth of ultrasound, CT, MR and interventional radiology meant a struggle to re-equip and re-skill our own departments.

Apart from lymphography all the examinations described above result in two-dimensional images. The bones, soft tissues and any contrast material are projected together in a jumble onto a flat film. You need to know the three-dimensional anatomy that underlies the image in order to interpret this confusion. Almost invariably in TV dramas chest X-rays are placed the wrong way round on viewing boxes – to the extent that it seemed deliberate to me. I wondered if the props department knew that the heart should be on the left and so put the chest X-ray up that way not realising the heart is not on their left but on the patient’s left. A radiologist looks at a radiograph as if they were looking at the patient’s body from in front. The crucial skill to acquire early on is knowing the patient’s left from their right – otherwise disaster can ensue. Similarly, in cross-sectional imaging, by convention, the body is viewed from below, as if looking up at the organs from the feet. Here again, the organs of the right side of the body lie to the left of the image.

A radiologist of my vintage would be subjected to a dose of radiation amounting to roughly twice the background dose we all get in our normal lives. (People in Cornwall and Aberdeen get more because of the radioactive rocks in these places.) This is actually a minimal increase in risk as we all have about a 40% chance of developing cancer anyway. Nevertheless we all wore film badges on our belts that monitored our dose and got togged up in heavy lead aprons to do screening lists.

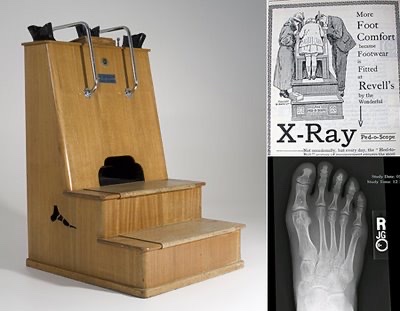

I am old enough to remember shoe shops with X-Ray screening equipment that allowed you and your mother to view your toes wiggling away inside your new Start-Rites. I’ve seen my own toes several times this way. When I showed an image of this equipment during a lecture towards the end of my career it produced a gasp of horror from the young audience.

Before the advent of ‘dry’ processing using film cassettes, X-ray films were developed in fluid-filled tanks in a darkroom. These ‘films’ were originally glass photographic plates. When I started radiology request cards at the Royal Infirmary were still being stamped ‘WPP’ standing for ‘Wet Plate Please’ even though we had on long since moved to dry films. A ‘wet plate’ meant an urgent examination that was to be returned to the ward or clinic with the patient. If you were on the rota for ‘top bench,’ reporting films as they came through, wet plates were prioritised. The reports were typed by a secretary who sat beside you at ‘top bench’ transcribing your immortal prose. A carbon copy was kept on the back of the original request card and the top copy sent back to the ward with the films. The cards were filed manually in the department.

Films regularly went missing. Comparison with any previous films a patient might have had is invaluable for interpretation. The clinicians involved thought that they should keep the films – either in their ward or in the boot of their car. We thought they should be filed systematically in our department and so be available for comparison. Finding films, a running sore for everyone involved, was eventually fixed by the arrival of digital storage.

Paradoxically, plain films, while a simple technique, are very tricky to report. You require a vast mental archive of normal and abnormal appearances in order to interpret what you are seeing. There are two kinds of error in reporting an examination. You can either fail to see the abnormality or misinterpret that abnormality and issue a misleading report. There are sins of omission and commission. For a long time we junior trainees required to have our work checked by our elders and betters, a senior registrar or a consultant if you could find one.

Like the fieldcraft of birdwatching, it is not enough to look at something, you have to understand what it is. The whole problem with birds is to make an identification. Is it something common or rare? – to see what is different in each species. Likewise in radiology you need experience to recognise what you are looking at. You require a a mental library of all the variations in normal appearances. In radiology there are textbooks of ‘normal variants’ that have to be learned (Keats). To the tyro the ability of the experienced radiologist to recognise pathology instantly – like an old friend – seems almost mystical.

Before digital imaging radiology departments kept hard-copy film libraries where interesting cases were stored for teaching. Pilfering for somebody’s private teaching collection or borrowing by clinicians who ‘forgot’ to bring the films back was a constant threat to the collection. Periodically some hapless junior would be given the task of sorting out the entropic chaos of these places. The keen ones enjoyed doing it and benefitted from it. When I did my trawl through the archive at the Western I found some ancient films in disintegrating bags. One of them showed an elderly man’s forearm with a fracture. In addition, there was a metallic foreign body in the soft tissues close to the elbow. I turned the bag over to see why this had been kept. In pencil in beautiful copperplate script someone had written:

Gunshot injury. Shot by Robert Louis Stevenson!

There was no other information.