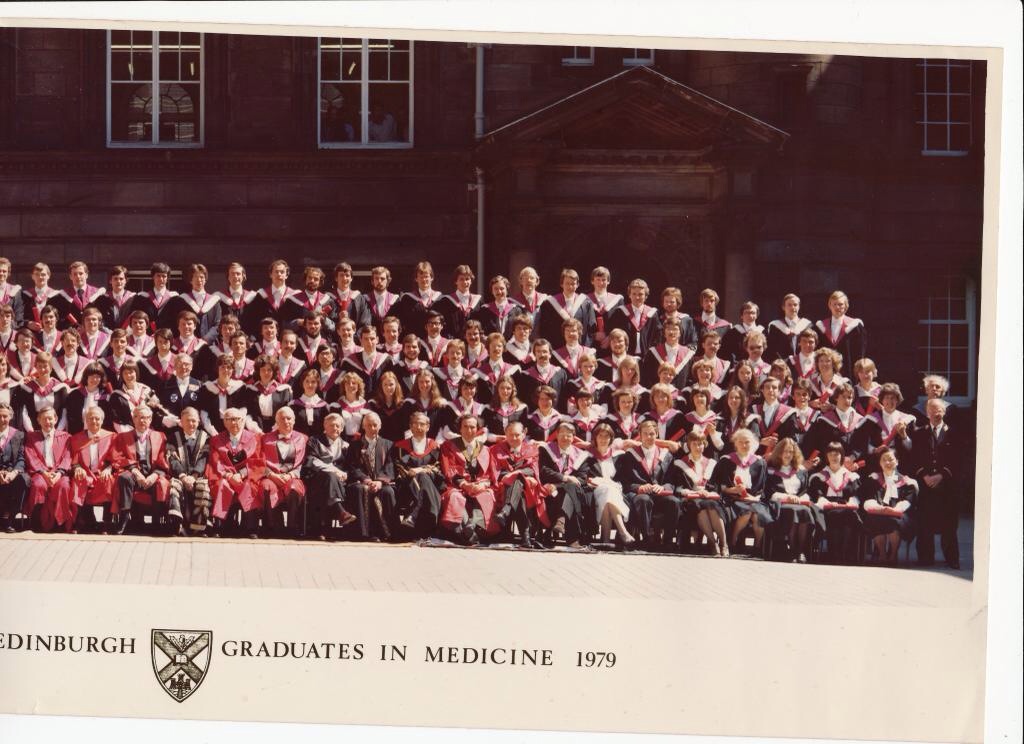

I

As my premature departure from the training scheme in psychiatry approached I attended my last Grand Round in the ivory tower of the Royal Edinburgh Hospital. These events consisted of a couple of half-hour talks or case presentations from psychiatrists of variable seniority given to the assembled hospital staff. Earlier in the year I delivered one of these talks, on the topic of the madness of George III.

The most memorable presentation during my year on the scheme concerned a patient who came to the attention of the authorities after a fire at his digs. He was an Australian national, not known to psychiatric services. Suffering from chronic varicose leg ulcers, he was entitled to various benefits. He moved around the country, signing up with local GP practices and receiving money to pay for his accommodation. Rescued from the fire and suffering from smoke inhalation he was admitted to a general medical ward.

In the course of his admission it became clear to the medical staff that he harboured a number of unusual beliefs. He thought himself to be a Venusian who, as a child, had come to earth in a spacecraft. Cut off from his people and culture, he wished to preserve the memory of his home planet and spent his time in libraries filling notebooks with drawings of Venusian cities and landscapes and writing copious tracts in his native Venusian. The books were of some artistic merit. He was perfectly happy and had never been treated with any antipsychotic medication. Nevertheless, he was clearly a schizophrenic with complex delusions. The question arose; should he be treated? Unlike Richard Dadd the patricide, he had done no one any harm and the general feeling was that he shouldn’t be medicated.

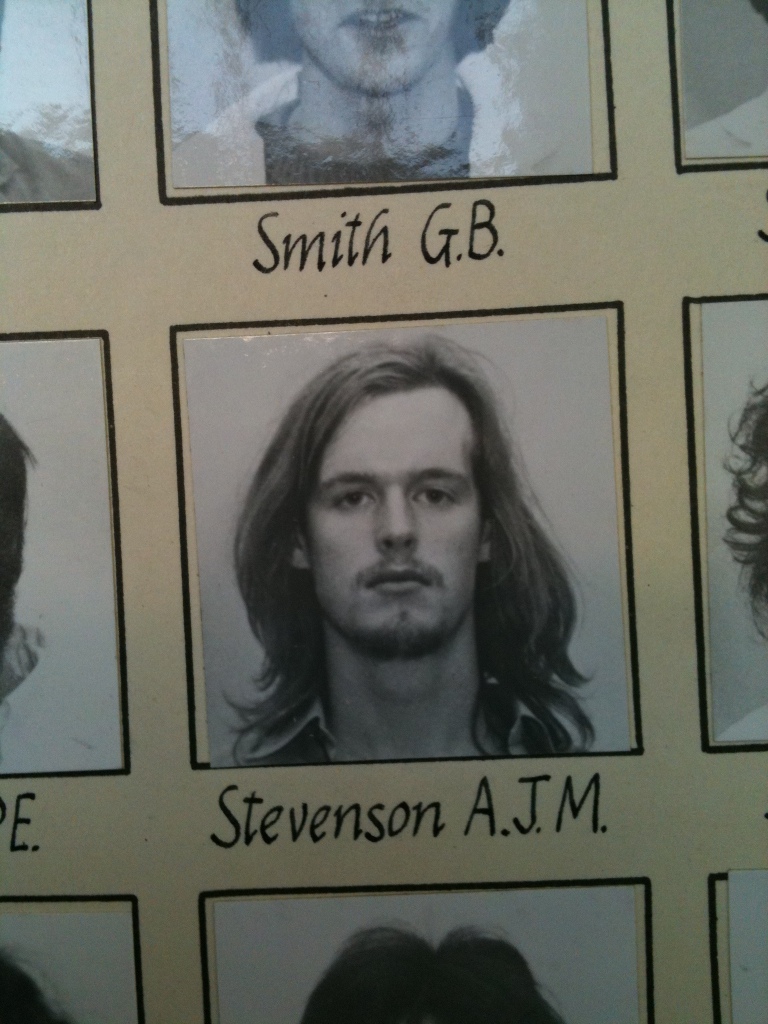

In contrast to that intriguing case, the last talk I attended was not very engaging, and bored, I contemplated the wooden writing tablet in front of me.The tablet is the shelf where you rest your notes. It was covered in graffiti incised into the surface with ballpoint pen; a jumble of initials, dates and scurrilous comments left by medical students over the years. On an impulse, knowing I was leaving, I wrote, ‘Psychiatry is bunk.’ Then, thinking it would be craven to leave that comment anonymously, I added ‘AJMS 83-84,’ confident that no one would actually identify me from such cryptic information.

How did I end up a square peg in that particular round hole? A year earlier, confronted by the necessity of doing a MD and probably a fellowship abroad in order just to stay in general medicine, I decided to follow my schoolboy plan to become a psychiatrist. In my boyish imagination this would be the perfect combination of science and the arts – and it would allow me to stay in Edinburgh for a bit longer.

It was not an entirely unconsidered choice. At secondary school I had read some clinical psychology books and my fifth year student elective in 1978 had been in psychiatry, with Eve Johnstone at Northwick Park Hospital in Harrow, a heavily academic unit. She was later to occupy the Chair at Edinburgh. I was sent off to nearby Victorian asylums to carry out Hinton and Withers Present State Examinations on chronic schizophrenics as part of an on-going study of ‘dementia in dementia praecox.’ Dementia praecox is the old name for schizophrenia. The test included things like serial 7s (subtracting 7 from 101 until you reach zero) and remembering the Babcock Sentence: One thing a nation must have to be rich and great is a large secure supply of wood.

This didn’t turn out to be the onerous task I had anticipated since most of the patients couldn’t even tell you their name. One cynical charge nurse was amused when I turned up to interview an aged Polish patient. ‘She hasn’t said a word in English for 30 years!’ he cackled. In one institution I discovered a piano on a stage in a little concert hall (nineteenth century asylums were very well appointed) and filled in the time playing that until I was picked up and taken back to Northwick Park.

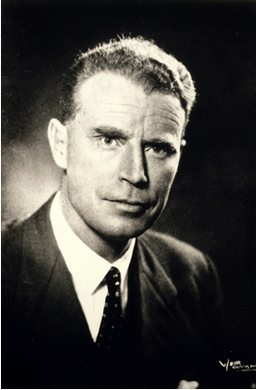

By 1983 I had completed three years in general medicine and qualified as a physician. I had considered radiology for a career but the idea of joining a non ‘bed-holding’ specialty with its perceived low status put me off. Having said that, the image of psychiatry within the profession wasn’t an entirely positive one either. However, armed with Membership of the Royal College of Physicians I was confident the psychiatrists would have me. On the day of the interview everything went to plan. When they asked me why I wanted to do psychiatry I answered jokingly (but secretly truthfully) that watching Gregory Peck in Hitchcock’s Spellbound had inspired me. That went down well.

Previous new jobs had always begun in August, but for some reason the psychiatry training scheme started in October. This left me with two months to kill. I decided not to do locum work but instead ‘sign on’ and attempt some creative writing at the state’s expense. The break kicked off with a week in New York visiting old friends. We went to a chic Japanese restaurant in Midtown Manhattan on the night Yoko Ono happened to be eating there. The food was excellent but after I returned to Edinburgh I became ill. Assuming it was a simple tummy bug I attempted to tough it out but I started losing weight and couldn’t keep anything down. Soon I had symptoms typical of malabsorption and I thought I had contracted something truly awful. Making my way up the Mound to see a Festival performance of Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis at the Assembly Hall I found I could barely walk and had to stop and cling onto the railings.

My GP was confident he knew what was wrong with me. He said he himself had contracted the same condition in St Petersburg and that New York was another ‘hot spot.’ Sure enough, live Giardia lamblia, a protozoan infection, were found in my specimen. Under a microscope they look like animated badminton rackets. A course of metronidazole and a home visit from a Public Health consultant followed. This left me very little time to write The Great Novel. I roughed out a plot, the usual semi-autobiographical guff, and showed it to my then wife who pronounced it awful. Early one morning, unable to sleep, I burned it in the living room fireplace.

II

October duly arrived and relieved of the burden of creativity I reported to the Royal Edinburgh Hospital in Morningside. I found I was attached to the Professorial Unit, Ward 2. I appeared to have been diverted there from an original placement in psychogeriatrics. I wasn’t given any reason for this change but the rumour was that Professor Kendall had something to do with it.

By this time R.D. Laing’s novel theories about the genesis of psychotic illness had been largely discredited but the rivalry between the psychiatrists who practised talking therapies, and the peddlers of pharmacological treatments raged on. The intake of trainees reflected this. We were all aware of each other’s backgrounds. At that time I was driving an Audi Coupé and one of my new colleagues remarked on this. ‘When we saw your car we thought, here comes the medical model,’ she sneered. I suppose I did favour a more physical approach but I resented being judged on such flimsy evidence.

One notorious study, much discussed then, compared the treatment of three groups of patients with depression. One group received psychotherapy, another psychotherapy combined with antidepressant drugs and a third only drugs. The patients who only had drugs did best while those on psychotherapy alone had the worst outcome, from which it was concluded that adding psychotherapy to drugs actually reduced their benefit!

I began to learn basic psychiatric information such as the difference between a neurosis and a psychosis. A patient with a neurosis comes to you asking for help because they are distressed by their symptoms. Perhaps they can’t go outside, or stop worrying, or stop checking things or stop washing their hands. They are upset by these thoughts and perceive them to be a problem. A psychotic patient on the other hand has no such insight into their much deeper delusions. They are unaware that they are being irrational and help is usually sought by their relatives – or the police. It did seem to me to be interesting work, at first.

Ward 2 where I was based contained a wide variety of cases severe enough to require inpatient assessment. There were the usual schizophrenics and psychotic depressives plus a few very severe neuroses including gravely ill anorexics and bulimics. I had just missed the very long admission of the ‘Fish Man’ a teenager so crippled by obsessional rituals he could no longer function. He was fixated on fat in his diet and insisted on boiling up fish to eat on the ward then scooping off any fat he found floating on top. He would time when to start and stop eating using a stopwatch then calculate his calorie intake generating reams of statistics. The ward had stunk of fish for weeks. His father kept telling the staff his son was ‘professorial material’ and seemed unable to grasp how handicapped he was.

Professor Robert E Kendell was the senior consultant on Ward 2 and occupied the Chair of Psychiatry at Edinburgh University. He would go on to become Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at Edinburgh, President of the Royal College of Psychiatrists and eventually Chief Medical Officer for Scotland. He was an impressive man of conservative appearance and a somewhat unnerving presence. His inaugural address considered whether you needed a medical degree to treat mental illness. His conclusion was that if you were going to prescribe drugs or treat conditions that were the result of degenerative changes in the brain, you did. However if you were purely acting as a psychotherapist, you didn’t. He was pragmatic and used electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), where appropriate, without hesitation. I witnessed its transformative effects in very severe depression. All trainees were expected to administer it (to the non-dominant hemisphere) assisted by an anaesthetist.

My first patient interview was with a young male paranoid schizophrenic. He had been visiting brothels in town and as his illness progressed he had been involved in some violent behaviour which brought him to the attention of the police followed by his admission. As recommended in the textbooks I asked him how he was feeling. After a pause he said, ‘You look like a giant.’

‘And how does that make you feel?’ I asked.

‘It makes me feel like killing you.’

Alone in the room with him I glanced at my watch. ‘Well, I think it’s time for lunch,’ I offered cheerfully. ‘Why don’t you pop back to your room?’

Another early case was Lawrence, an elderly Jewish man who was admitted with depression. He had no appetite and had become emaciated. The skin in his axillae was deeply pigmented. I was quite convinced he had advanced malignancy and presented my diagnosis to Professor Kendall. He himself was a former physician, a neurologist, but made great show of deferring to my more recent qualifications. I thought he might be mocking me. Reluctantly he allowed me to transfer Lawrence to the Royal Infirmary for investigation, while he himself remained convinced the problem was psychotic depression. About two weeks later Lawrence returned from the Royal, the physicians having found nothing physically wrong with him. ‘Now will you let me treat his depression?’ asked Kendall with a twinkle in his eye. Lawrence eventually went home after a course of ECT completely recovered and back to his normal weight. Even his pigmentation resolved.

Unfortunately as the year wore on we trainees were given only minimal supervision and the lecture course seemed random and impractical. Nevertheless we were expected to see and manage both in- and out-patients ourselves. The nursing staff at least were helpful and pragmatic. An acute psychiatric ward is a very hands-on place to work. It takes enormous skill and patience to manage such challenging patients. On the morning housekeeping ward rounds with the nursing staff there was no point labouring technical diagnostic points. You needed to know how things were going – but briefly. ‘How’s John then?’ would be greeted by, ‘Still very mad.’ There was no need to say more. But this practical approach could be misinterpreted. A new social worker straight off a university course arrived on the ward. She was full of good intentions and theory but no experience. After her first ward round she turned to me and said, ‘I look around this place and I ask myself, who is giving these patients love?’

I loved the elderly secretary on Ward 2. Apart from being a first rate source of gossip, she took shorthand then typed up my letters, improving my prose style in the process. It was my only experience of dictating to a human being, all other jobs made use of small hand-held tape recorders. As she scribbled away, her cigarette never left her mouth and the smoked curled up through her glasses leaving her brow and forelock lightly tar-stained. She knew everything about the Royal Ed and the psychiatrists who worked there going back decades.

Arch humour was the norm among the experienced nursing and medical staff. It often took the form of a feigned callousness or deliberate contrariness. I claimed that if you said good morning to someone at the Royal Ed you’d be asked what you meant by that. One aphorism circulating in 1983 was that ‘neurotic’ had become a term of endearment. It was being applied to almost everyone and hence had become quite meaningless.

That Christmas of 1983 there was a Ward 2 night out to the notorious Armenian Restaurant in Holyrood where the highly eccentric owner insisted we all get up and dance to Armenian folk music. RE Kendall got very enthusiastic, attempting a sort of Cossack dance and ended up crashing into the stereo system.

Studying psychiatry was a social minefield. Asked what you did for a living at a dinner party the response to the information that you were training in psychiatry was unpredictable. Your dining companion might launch into a prolonged history of their sibling’s mental health issues assuming you’d be fascinated – or else they might become hostile because of some previous negative experience or philosophical dislike of the specialty. ‘Who decides if someone is mad? I mean, what would happen if you decided I was mad?’ was a common challenge. I would try to explain that the patients I dealt with were mad in the colloquial sense. A few brief moments in their company would convince any lay person of their insanity. They were obviously mad, not matter-of-opinion mad. I started saying simply that I worked in a hospital.

Within a few weeks I had become convinced that psychiatry was the wrong career move for me. This disaffection added to a background dissatisfaction with life and relationships in general. A deep gloom descended. I decided to look elsewhere for a job as soon as the opportunity arose but in the meantime I carried on in case I was mistaken and simply suffering from my own little unhappy psychiatric disorder.

Ward work and lectures continued. I began to get the hang of dealing with psychotic patients. Once they recovered they usually wanted nothing more to do with you, even crossing the street to avoid you as if merely being seen with you in public was humiliating. One patient in particular illustrated this problem.

Keith was a clever boy from a modest social background, the first of his family to go to university, and his parents’ pride and joy. After starting the first year of his physics course at Edinburgh University he experimented with marijuana at a party. This seemed to trigger his first bout of psychotic illness. It took the form of what used to be called schizoaffective disorder, a psychosis that combines features of schizophrenia and manic-depressive psychosis. Keith formed the conviction that he’d discovered the Fifth Force in the universe. He was unable to sleep.

Clearly unwell, his parents had taken him home from university but shortly after that he interrupted a physics class at his old high school, one that contained his younger brother, and addressed the class on the subject of the Fifth Force. The physics teacher didn’t like to stop him, perhaps imagining that like the sleepwalker myth it would be a mistake to interrupt him. Having come to the attention of the mental health services in this way he was admitted to the ward. His parents were very unhappy about it, feeling it would damage his career prospects. Eventually they demanded his release from the ward. Reluctantly we agreed, but his symptoms deteriorated further culminating in him vandalising the family car after which he was readmitted, this time under Section 28 of the Mental Health Act 1959.

Keith was ill for many weeks. His parents were devastated. When I arrived on the ward in the morning he would shout his delusional ideas in my ear and demand his release as I walked down the corridor. Each night I prayed, ‘Please make Keith better tomorrow.’ Eventually the storm subsided. Some insight crept into his conversations with me and finally he was released to out-patient follow up. He eventually defaulted from review, but on his last visit to out-patients he informed me that he didn’t believe any of the things he said to me while on the ward. ‘I just said that stuff to wind you up. I was laughing at you,’ he said, scornfully.

Meanwhile, my cohort of out-patients with neuroses began to grow. Every time I suggested they might be well enough to return to their GP for onward care they threatened to harm themselves. On one of the rare occasions I got to discuss this with my consultant he told me I was ‘encouraging dependency.’ My archaic medical model-type thinking tripping me up again.

III

However unhelpful, the lecture course was at least interesting. One highly anticipated session was the annual talk on hypnosis given by Professor Ian Oswald. The rumour was that he would attempt to hypnotise the whole class of trainees. Exciting stuff. Came the day and the Prof’s introduction:

‘Now, we all know that it’s easy to make fun of things and have a bit of a laugh, but we will never learn anything with that sort of approach, so I would like you all to take what is to follow seriously so that we may benefit from the experience.’ A frisson ran round the room. I was sitting next to my old university friend Jamie, also on the training scheme. Prof Oswald continued at a brisk pace. ‘Would you all now put both your arms above your heads and clasp the fingers of your hands together as hard as you can. That’s good. Now keep pressing as hard as you can. I’m going to suggest to you that when I tell you to unclasp your hands you will be unable to do so, no matter how hard you try… OK, now unclasp your hands.’

Jamie and I and most of rest of the class immediately released our fingers and looked around, relieved to have retained control of ourselves. However, a couple of our number were stuck with their hands locked together. Prof Oswald homed in on his victim, a quiet, diffident female colleague. He told her she would now be able to release her hands, which she did, then he told her to come to the front of the class. He sat her on a chair facing us and placed her in some kind of waking trance. He demonstrated a number of subjective phenomena such as telling her she could feel nothing on one side of her body. Finally, he woke her up and asked her if she thought she’d been asleep. She said no she hadn’t, she had been fully aware during the entire experiment but unable to do other than comply with his instructions.

Hypnosis as a public entertainment was legal in Scotland. Some of these performers offered other services such as cessation of smoking. One client became suspicious of the therapist’s motives when he suggested they meet at her home. Her brother-in-law was a policeman and arranged for officers to be present secretly inside the house. Although the hypnotist was arrested for attempted sexual assault and came to trial he got off on the basis that the police tactics amounted to entrapment. Prof Oswald was an expert witness at the trial. Fascinating stuff.

A less enjoyable incident occurred during a lecture on psychotherapy from Professor Henry Walton. Walton is now famous for his modern art collection, donated to Edinburgh galleries. At that time he was better known for his thoughts on the suitability of medical students to do psychiatry based on their ‘tolerance of ambiguity.’ He had authored a popular science book called Know Your Own Mind. I remember a lecture he gave to us as medical students which involved him taking a sexual history from some poor man in a dressing gown in front of a large audience. The man stared at the floor throughout as Walton asked about masturbation etc. and didn’t answer him. ‘Do you always experience such difficulty discussing sexual matters?’ asked the professor. I did a cartoon of this appalling scene and questioned whether I wanted to be a doctor at all.

Walton was notorious within the medical school for an episode of shoplifting in Harrods which he eventually attributed to a fugue state. When asked by the trial judge what a man in his position was thinking of being caught shoplifting he said, ‘I don’t know, I must have been mad.’ Private Eye pounced on this exchange. A period of gardening leave followed, incompletely observed, then he was reinstated. By the time I attended this lecture I was battle scarred and thoroughly disillusioned with the training scheme. At the end of his exposition Prof Walton invited questions. I raised my hand.

‘Professor, we are very junior trainees who have only a few months of experience but on-call we are invited to see acute patients and offer short term psychotherapy if appropriate. They often have massive thick notes indicating they have seen many, more experienced, psychiatrists in the past. I’m afraid I feel a bit of a fraud offering my services to them.’ The professor’s face darkened, ‘If you said that to me in an examination I would fail you and trust you would take up some other branch of medicine.’ I thanked him for his reply.

About a week later I bumped into Chris Freeman one of the other consultants on Ward 2. By this time I had moved to Ward 4 for my next six month attachment.

‘I wanted to speak to you Allan,’ he began.

‘You want to know how I’m getting on in Ward 4?’ I offered cheerfully.

‘No, I don’t care about that,’ he said (more psychiatric humour) ‘I wanted to talk to you about what the Prof said to you in the lecture last week.’ Somehow the exchange had come to his attention.

‘I want you to know that it will have no bearing on your future career in psychiatry.’

‘No I suspect it won’t, but thanks for telling me,’ I replied.

On-call work at the Royal Ed could be challenging. Two trainees were available on any given evening, one was based at the Royal Ed itself. After 10pm the other trainee would make their way to Craighouse Hospital, a spooky Victorian long-term asylum on a nearby hill that looked more like the set for a horror movie. It had originally been built to house wealthy patients and their servants in gothic luxury but had since become an NHS facility. Sleeping there and hearing the ‘noises off’ was unsettling but at least you weren’t at the mercy of acute admissions.

Back at the main hospital you waited to be summoned. There was a mixture of outside referrals and in-patient crises to deal with. One night before my colleague had left for the Addams Family Mansion I got a phone call from switchboard. I had a call waiting. A weary-voiced woman informed me that she thought she’d killed her baby. She refused to tell me who she was or where she was calling from. In the background a large dog barked incessantly. Despite the information that ‘the wean’s no’ breathing’ the woman wanted to discuss other issues. I covered the mouthpiece and whispered to my colleague, ‘Can you trace this call?’ She shrugged then picked up the other phone in the room. Eventually the woman became impatient with my amateurish advice and rang off. ‘You’ve been nae help tae me!’ she chided. My colleague told me the police had traced the call.

Half an hour later the police called me. ‘We’re at the property now doctor. The door’s locked and we can hear a dog barking inside. How should we proceed?’ I was well into uncharted waters now. ‘I don’t know. You’re the guys on the spot.’ I said. ‘All I know is that she claimed to have killed her baby.’

‘OK, doc we’ll let you know what happens.’ They rang off.

About 15 minutes after that they were back on the phone. ‘Eh, we broke down the door and there was just a dog inside the house, no baby, and now the owner’s come back from the pub. She’s very unhappy about the damage to her property.’

In-patients would often harm themselves overnight. At times basic first aid was required but often the damage was more serious. A rugby player, a front row forward with a local club, was admitted with his first psychotic illness. The ward called me to say he had stripped himself naked and was jumping off his bed onto the tiled floor head-first because, ‘God is telling me to have epileptic fits.’ The burly charge nurses from the high security Ward 10 were already on the case and I was required to complete the formalities.

When I got there the man seemed calm and I began completing a Section 28 and countersigning the drugs that had already been administered to the patient by the nurses. The patient and his escorting posse walked down the ward and out of sight towards the stairs. Suddenly a young female nurse came running back towards the duty room shouting for me to come quickly as there had been ‘an incident.’

The patient had made a break for freedom at the top of the stairs, the nurses had restrained him and hauled him to the floor. In bare feet, one foot had stuck on the tiled floor as they piled on and he had sustained the worst fracture dislocation of his ankle I had ever seen. The foot was up one side of his tibia, the skin stretched tightly over the bone end. Despite this appalling injury the prop forward was still trying to get up! More sedation was given and I hurried off to phone casualty at the Royal Infirmary. ‘I’ve got an interesting one for you,’ was my opening remark.

By 4 am after several other calls I had fallen asleep in the horrible on-call room. There was a plastic sheet under the actual sheet which made it slide about in an unpleasant way and the big cast iron Victorian radiator was broken, stuck at maximum flow. The room was sweltering and you had to open the window wide to try to cool off. The phone rang. It was Ward 10. ‘Can you come and write up some analgesia for your patient with the broken ankle?’

‘What? He’s not at the Infirmary?’

‘They bivalved his plaster and sent him back. He’s OK, it’s just that he’s awake now and in quite a lot of pain. He’d had so much sedation before he went over there they didn’t give him anything else.’

After Christmas I was still miserable and wanted to escape from this first career misstep. Seeking certainties I applied to the radiology scheme and was accepted. I decided to complete the full year in psychiatry rather than bail out to some other temporary job. After all, I might change my mind.

I completed my year in psychiatry with six months in Ward 4. The senior consultant there, whom I won’t name, was less helpful than REK. Once when reminiscing about his career he said, ‘At the time I had a number of sexual skittles in the air,’ a phrase that I’ve never forgotten. It proved pointless asking him for help with my now huge out-patient load.

Towards the end of the Five Nations rugby tournament of 1984 Scotland found themselves in a Grand Slam decider with France at home. My brother got us tickets at the last minute but I was on call that weekend. In the registrar’s room I spotted the new trainee who had just arrived from Singapore. I asked him if he would swap on-call, and having nothing to do and no interest in Rugby Union, he agreed. I got to stand on the North Terracing and witness a Scottish victory. Jerome Gallion the French scrum half was knocked unconscious in a collision with David Leslie and admitted to the Infirmary for a CT scan in the department I was soon to join. It was the only time I’ve seen supporters throw their hats in the air.

Exeunt

When Jamie and I announced our departure from the scheme there was a certain amount of reflection on the part of the trainers. We were asked to explain ourselves at the Friday afternoon ‘sensitivity meeting.’ Having secured new jobs we did not really want to explain ourselves and instead blamed personal issues such as our emotional unsuitability to the cut and thrust of mental health. Beyond that Friday afternoon session I was summoned to Professor Kendell’s office to explain myself. He seemed disappointed in me and I felt uncomfortable. He plonked me in a very low armchair then sat perched on his desk high above me.

‘Why are you leaving us, Allan?’

I struggled to form a sensible response. ‘Well, I find the patients awful,’ I offered lamely, reluctant to say that I felt completely unsupported.

‘What’s awful about them?’

‘Well they seem to get better or worse irrespective of what I do for them.’

‘You don’t find them interesting in themselves? You will be aware that before psychiatry even existed as a science the great descriptions of psychological illness were found in literature; in Shakespeare and Dickens. What interests you in medicine?’

‘Structure and function I suppose,’ said I.

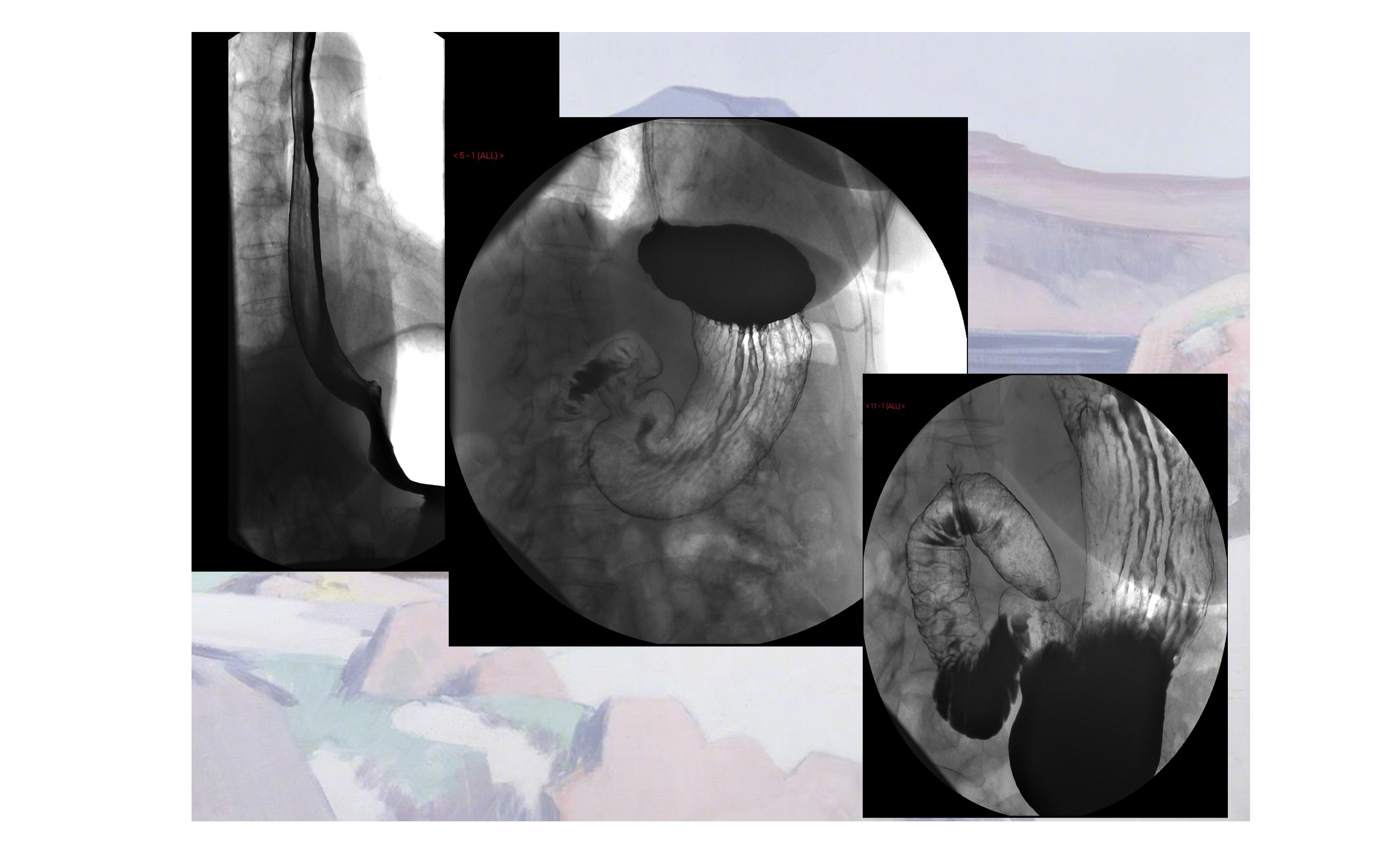

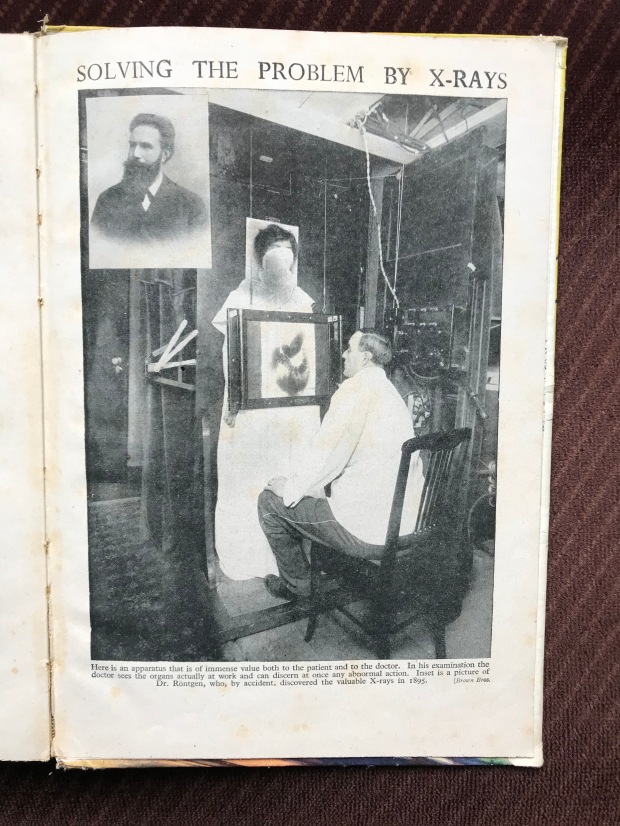

‘Well, we could be a hundred years away from that in psychiatry,’ said Kendall. ‘And why radiology for goodness sake? Radiologists lead an etiolated existence.’ He sighed. ‘Write to me and let me know how you get on.’ With that I was dismissed and went home to look up etiolated.

After a few months of happy structure and function in radiology – the plumbing and wiring of medicine – I decided I should indeed write to REK and tell him that I was satisfied I’d done the right thing. I sent him an anodyne note thanking him for his counsel and the reference he had written for me.

A few days later I got a reply:

Dear Allan,

I do hope you settle down in your chosen metier soon. Should you have any doubts about your decision I suggest you recall what you inscribed on one of our lecture theatre desks not six months ago: Psychiatry is bunk. AJMS 83-84.

I trust this was an accurate reflection of your feelings at the time.

Robert E Kendall.

I was horrified. When I told his friend Judy Greenwood about it she dismissed it, ‘Oh he’s a bugger,’ she laughed. ‘I’ll have a word with him.’

Years later when I had become a consultant radiologist I discovered REK had been taken off my ultrasound list by a senior colleague who felt I wouldn’t want to scan my ‘old boss.’ Some time after that I met him leaving outpatients and he recognised me. ‘You had a lucky escape Prof. You were nearly on my ultrasound list.’ I said, grinning. ‘You’re the one who missed out,’ he replied. ‘I am an interesting case.’